Jane Qiu is a former postdoc turned reporter. She is the only reporter to interview Shi Zhengli post-pandemic. Jane leaned towards a natural origin (aka zoonati), but reported helpful facts:

We met for lunch and then went for a walk in a nearby park. A few days later, I visited the institute’s city campus in central Wuhan—approximately 12 miles from the suburban site that the WHO team later toured. Shi’s lab was on the second floor of a solemn-looking cream-colored building. The main room had rows of benches with weighing machines, polystyrene ice boxes, and desktop centrifuges. Bottles of chemicals and solutions were tightly packed on the shelves. One student was typing away on a computer, while another was pipetting a tiny amount of colorless liquid from one test tube to another. The scene gave me a sense of déjà vu—I’d spent a decade working as a molecular biologist, including six years as a postdoc. It reminded me of my days in the lab.

“It’s probably not that different from where you worked,” said Shi, as if she could read my mind.

Shi is petite, with short wavy hair that is neatly combed. Her voice is high and light, with the sparkle of a soprano (she is an amateur folksinger). That day she wore a beige sweater and blue jeans. As we went on to other parts of her lab—the deep freezers that held bat samples, and the rooms for culturing cells in petri dishes—Shi explained that her team had about three dozen researchers. That’s a lot for a Chinese lab, but it’s not the gigantic operation that many outsiders imagine. “I do not have an army of researchers and unlimited resources,” she said. Until the pandemic hit, coronavirus research was not a trendy subject and could not easily attract funding.

Shi is one of the rare breed of virologists who are just as comfortable in the field as in the lab. She grew up in a small village in central China’s Henan province and spent most of her childhood roaming the hills. She doesn’t regard herself as ambitious. When she graduated from the prestigious Wuhan University in late 1987, she told me, “I thought I had achieved my career goal and the next stage was to get married and have kids.” The main reason she went on to study at the Wuhan Institute of Virology was to stay in the same city as her then boyfriend. But as China invested in sending promising young scientists abroad to pursue doctoral degrees, Shi grabbed the opportunity.

In 2000, Shi got her PhD at Université Montpellier 2 in France. Studying there was an unusual decision since she didn’t speak French, and a difficult one because it meant leaving her young son behind in China; the stipend was not enough to support a young family. But the experience left a positive imprint; she particularly appreciated the Western culture that prized “critical thinking, independent-mindedness, and not following the crowd,” she told me. “You can’t do great science without any of these. This is what China really needs to get better at.”

At the time, lab leakers didn’t even know Shi’s BSL2 lab was located in downtown Wuhan, which is ~12 miles north of Dani Anderson’s remote BSL4 lab. Then Dani’s DARPA Defuse colleague, Ralph Baric, came up in their 2022 interview:

Shi didn’t have the necessary tools to do this type of genetic work, so in July 2013 she emailed Ralph Baric—a towering figure in viral genetics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill—about joining forces along those lines of inquiry.

The collaboration with Baric was not a close one, Shi told me: there was no exchange of laboratory staff, and Shi’s main contribution was to provide SHC014’s genomic sequence, which was yet to be published at the time. The findings, published in Nature Medicine in 2015, were surprising. It turned out that both the synthesized SHC014 and the SARS-CoV-1-SHC014 chimera were able to infect human cells and make mice sick. Both were less lethal than SARS-CoV-1, but—worryingly—existing drugs and vaccines that worked against SARS were unable to counter their effects.

Meanwhile, Shi’s team was attempting similar tinkering in her own lab in a project funded by the US National Institutes of Health, which aimed to probe the genetic ingredients that could allow bat viruses to cause SARS-like diseases in humans. But while Baric focused on the human pathogen SARS-CoV-1 in the Nature Medicine paper, Shi used only its bat relatives—mostly WIV1, the first bat coronavirus the team had isolated. Their real-world risk to humans was unknown. By the time the pandemic broke out, her team had created a total of a dozen or so chimeric viruses by swapping WIV1’s spike with its counterpart from newly identified sequences of bat coronaviruses, only a handful of which could infect human cells in a petri dish.

Baric supported Shi’s statement in his 2021 interview:

How did that chimeric work on coronaviruses begin?

Around 2012 or 2013, I heard Dr. Shi present at a meeting. [Shi’s team had recently discovered two new coronaviruses in a bat cave, which they named SHC014 and WIV1.] We talked after the meeting. I asked her whether she’d be willing to make the sequences to either the SHC014 or the WIV1 spike available after she published.

And she was gracious enough to send us those sequences almost immediately—in fact, before she’d published. That was her major contribution to the paper. And when a colleague gives you sequences beforehand, coauthorship on the paper is appropriate.

That was the basis of that collaboration. We never provided the chimeric virus sequence, clones, or viruses to researchers at the WIV; and Dr. Shi, or members of her research team, never worked in our laboratory at UNC. No one from my group has worked in WIV laboratories.

And you had developed a reverse-genetics technique that allowed you to synthesize those viruses from the genetic sequence alone?

Yes.

In other words, Baric could download and create Chinese viruses in his UNC lab, and he proved that Shi could not copy his methods. Ironically, this was Baric’s last interview with the media before DARPA Defuse leaked. In that document, Baric proposed to infect Chinese bats with SARS2-like genomes using Dani’s Wuhan BSL4.

Years later, Jane was set to appear in an upcoming documentary on natural origins alongside Peter Daszak, Linfa Wang, Shi, also of DARPA Defuse fame. But Jane went scorched earth in a recent Bluesky thread, which is copied and pasted below:

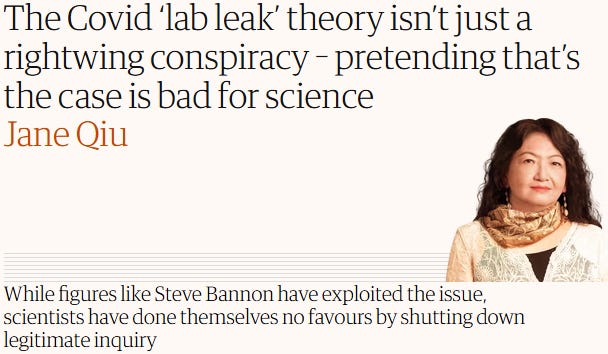

Why does the COVID origins debate remain so polarising and acrimonious?

What does this say about the state of science & the public discourse of science?

My Guardian op-ed debut, from a sociological perspective, includes the backstory behind the film Blame.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/jun/25/covid-lab-leak-theory-right-conspiracy-science

A perplexing aspect of the controversy is that scientists continue to publish studies in leading scientific journals that they say provide compelling evidence for natural-origin hypotheses.

Yet, rather than resolving the issue, each new piece of evidence seems to widen the divide further. Why?

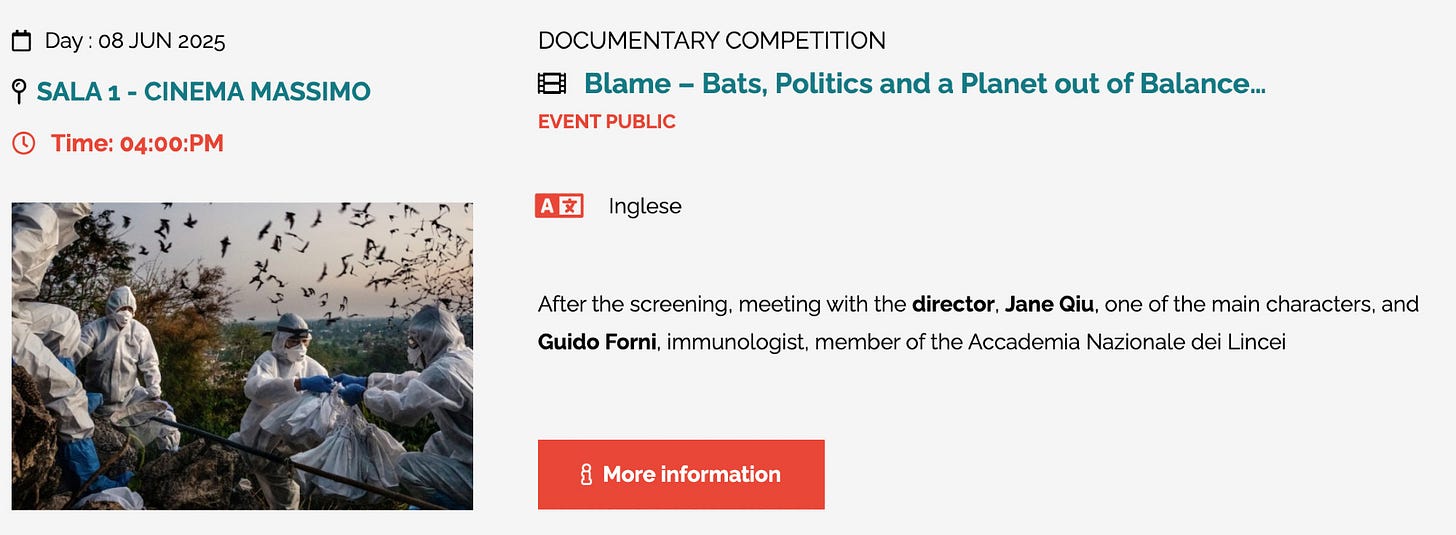

A new documentary by Christian Frei, titled Blame: Bats, Politics & a Planet Out of Balance, places the blame squarely on the so-called “rightwing fever swamp.”

According to Frei, it promotes misinformation and conspiracy theories about the origins of COVID-19 for political gain, confusing and misleading the public.

As a participant in the film (spending two weeks shooting in Thailand in December 2022)—and a journalist who has spent the past five years writing a book on the origins of emerging diseases—I must respectfully disagree.

At its core, the controversy is not a left-right issue, but a symptom of deeply entrenched public distrust of science. By framing it along the political divide—and by cherry-picking extreme examples to suit its narrative—the documentary does a disservice to the public interest.

It’s not hard to refute Frei’s claim because many outspoken left-leaning researchers are key drivers of lab-leak theories.

I also encountered numerous credible and well-respected experts on emerging diseases who also believe the question of COVID-19 origins is far from settled. Did COVID come from an animal market? Here’s what the new evidence really tells us:

A new study of genetic testing on samples collected from the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan does not provide definitive clues about the origins of COVID-19.

Far from a rightwing fever swamp, these scholars have lent scientific legitimacy to the debate. They are not convinced that the studies published in leading scientific journals supporting natural-origin theories are as compelling as the authors have claimed.

Such disagreements should be allowed. Few people would claim to know with absolute certainty how the pandemic began. Both sides are gathering evidence to support their case, yet neither can fully rule out the possibility put forward by the other.

This lack of clarity is similar to what we often see with most emerging diseases. We often assume that when people with different opinions are presented with the same evidence, their views should converge.

However, in science, evidence is almost always subject to interpretation. When the data are scarce, as in this case, interpretations can vary widely, and uncertainties are significant.

Some studies show that presenting more facts doesn’t always lead to agreement and can even widen divide—without needing to invoke irrationality or bad faith. Others demonstrate how individuals with diverse concerns, moral values, and attitudes toward authorities can interpret the same evidence in vastly different ways.

The core issue behind the COVID-19 origins controversy is fundamentally a crisis of trust, rather than a mere information problem. It reflects longstanding public anxieties over virus research. Strong emotions such as fear, anxiety, and distrust play a crucial role in human cognition.

Strong emotions such as fear, anxiety, and distrust can act as a powerful lens through which individuals process information and interpret evidence. Focusing solely on facts—a cornerstone of traditional science communication—can overlook systemic issues that undermine public trust in science.

The storm of public distrust in virus research had been gathering long before COVID. In 2011, two research teams sparked public outcry by creating more transmissible variants of H5N1, known as gain-of-function studies. This led to a pause in federal funding and the establishment of a new regulatory framework.

A sense of unease persisted, driven by the perception that virologists, funding agencies, and research institutions failed to address public concerns and anxieties, coupled with a lack of transparency and inclusiveness in decision-making.

COVID origins controversy sailed straight into the eye of the brewing storm. Did the virus originate from gain-of-function research that critics had long warned about?

How might even the slightest possibility of this have influenced the behaviors of virologists, funding agencies, and research institutions, prompting them to protect their reputations and preserve political backing?

The behaviour of scientists has further exacerbated the distrust. Some scientists assert evidence supporting natural-origin hypotheses with excessive confidence.

The intolerance toward dissenting voices is both staggering and disconcerting, leaving little room for questioning. Those who disagree are often labelled ignorant, contrarian, or acting in bad faith.

Even prominent virologists, epidemiologists, and experts on emerging diseases are deemed unqualified to assess the evidence if they do not view it as conclusive in support of the natural-origin theories.

Critics are often dismissed as “jealous” or accused of “bad-mouthing their colleagues behind their backs.” Even researchers leaning towards natural origins theories lament that some of their colleagues defend their theories “like a religion” [Vincent Munster quote].

No one embodies the crisis of trust in science more than Daszak, the former president of EcoHealth Alliance. A series of missteps on his part has helped fuel public distrust. He refuses to acknowledge his conflict of interest, and, unlike Shi, denies that his work with the Wuhan lab involves gain-of-function research.

Such errors of judgment and inappropriate behavior—not uncommon among scientists and not limited to the COVID origins debate—can affect how the public perceives scientists and the trustworthiness of their claims, as well as how they themselves interpret evidence.

Frei claims that attacks on EcoHealth Alliance and the spread of the lab leak have fueled distrust in science. It’s the other way round.

Public distrust in science, fueled by the unresolved H5N1 GoF controversy and a lack of transparency and humility among scientists, has driven increased support for a lab leak theory. As social scientist Benjamin Hurlbut of Arizona State University puts it:

The problem isn’t an anti-science public, but rather a scientific community that labels a skeptical public—grappling with legitimate trust issues—as anti-science or conspiracy theorists.

Trust cannot be manufactured on demand. It must be cultivated over time through transparency, accountability, humility, and relationship-building. Scientists must do more to earn it.

By framing the COVID origins controversy as a left-right issue, labeling all lab-leak supporters as conspiracy theorists, and failing to scrutinize the conduct of scientists, Blame misses the mark by a wide margin, risking further polarization of the debate and deepening public distrust in science.

Here’s the backstory behind the making of Blame in response

During my shooting in Thailand, I was shocked by Daszak’s fast and loose approach to facts, his refusal to acknowledge his conflict of interest, and his denial of his gain-of-function research in collaboration with the Wuhan lab.

I was equally shocked by Daszak’s constant self-promotion and its effectiveness. Frei seemed entranced by hero worship, apparently having lost all sense of objectivity and critical judgment. I felt strongly then, as I do now, that the film was a blatant piece of propaganda.

So, no, I don’t have any personal enmity toward Daszak. It really is nothing personal. It’s about critical thinking, fair-mindedness, professional integrity, and public interest.

I watched the film at the Cinema Ambiente festival in early June, along with just two dozen or so other people in an auditorium that could seat hundreds.

My Guardian op-ed was, in part, a response to the uncritical review of this blatantly biased film. I felt I had to set the record straight.

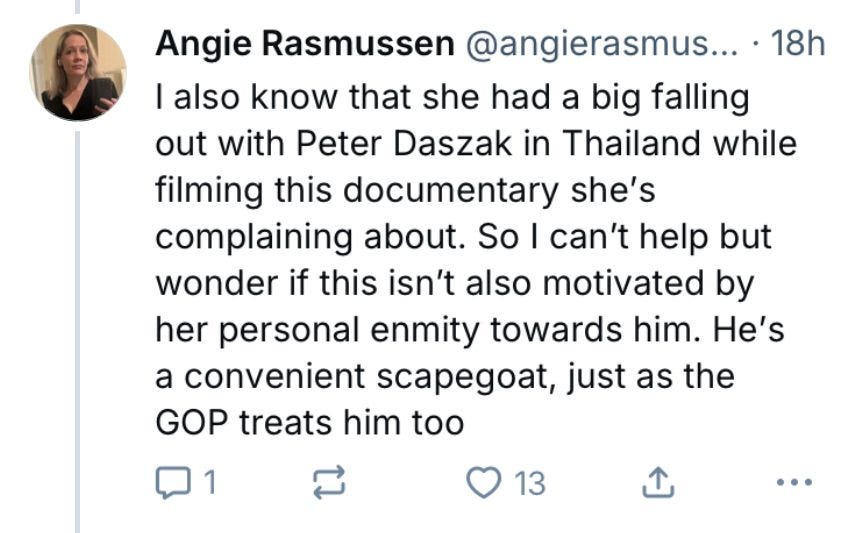

Did I not have reservations about speaking out? Of course, I did. I was terrified. I gave careful thought to the consequences of speaking out, such as facing the kind of bully and smears👇

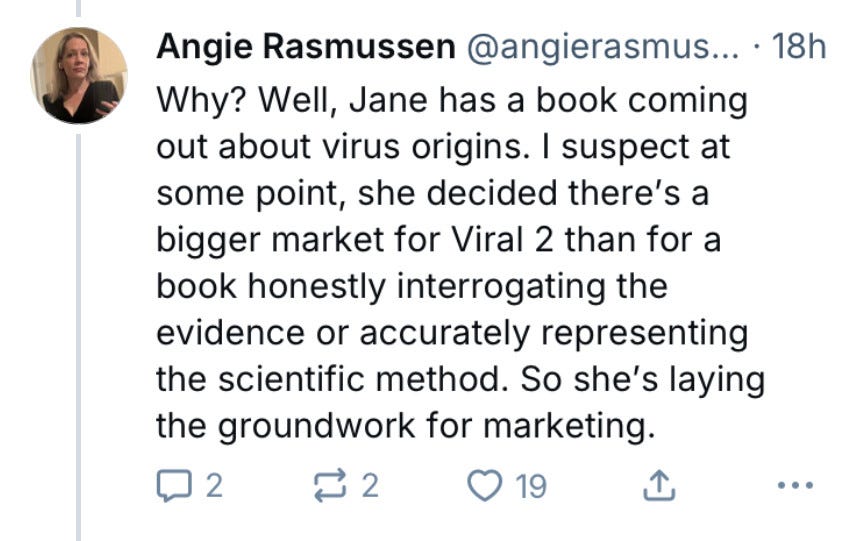

It’s Angie's evidence-free speculation that I have a book coming out, that I am laying the groundwork for marketing, and that I’m lying in order to sell my book.

These are serious accusations. They amount to defamation. But I’m afraid you're mistaken; I don’t have a book coming out. I’m a compulsive over-researcher. I’m still at the research phase.

I haven’t written a single word. It will still be years before I can submit the first draft. Would you consider deleting these two false posts?

I’m not sure if Angie — who previously praised my articles when she agreed with them — realised that she was actually helping me illustrate the very point my article is trying to make 👇, by demonstrating just how incredibly intolerant she is of views she disagrees with.

With due respect, engaging in a smear campaign against someone you disagree with goes beyond intolerance. It speaks more to your own integrity than to the person you’re attacking, Angie. It reflects what’s wrong with science. This kind of behaviour is what makes X so toxic.

Please help keep Bluesky a safe and civil place where people can freely express disagreements without fear of bullying and smear.

Let’s agree to disagree—respectfully and with civility. Let’s try to be the better version of ourselves.

Thank you, Angie [and thank you, Jane]