The Most Plausible Origin of SARS-CoV-2

Submitted to WHO's Scientific Advisory Group for the Origins of Novel Pathogens (SAGO) on May 21, 2025

We address the SAGO Committee to suggest the most plausible origin of SARS-CoV-2 and to recommend investigative priorities and action. Our scenario is based on extensive data of various kinds: forensic, genomic, epidemiological and others, all of which support the scenario we present. There is still considerable evidence to be revealed from records in the United States, not least because of a systematic pattern of fraud and concealment by US government officials and scientists on US government contracts. Our overarching recommendation is that this evidence should be brought to light and examined scientifically and objectively.

The virus was most likely created in US laboratories as a research project to create a model bat vaccine. The aim of the bat vaccine was to give immunity to Chinese horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus sinicus) against potential beta-coronavirus infections with spillover potential to US military personnel in East Asia. The two main US laboratories that likely created SARS-CoV-2 were at the University of North Carolina and the Rocky Mountain Laboratories of the National Institutes of Health.

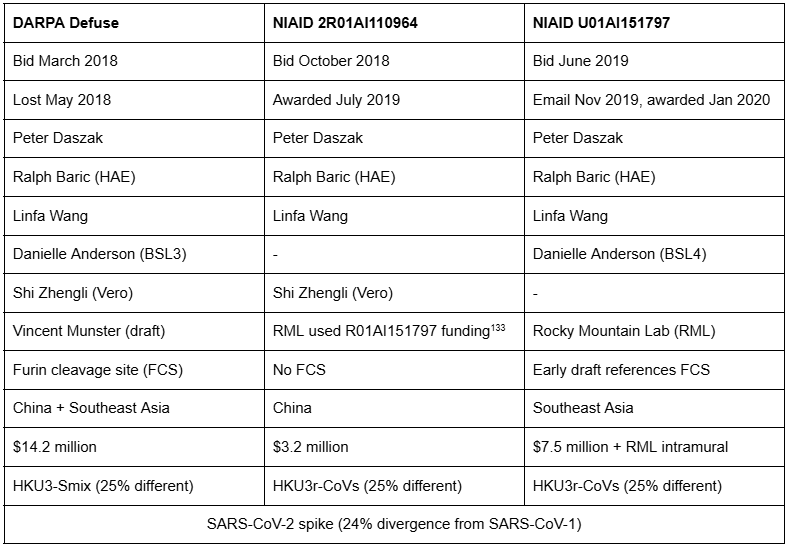

The aim of the research project was spelled out in the DEFUSE proposal made to DARPA in 2018. Though the DEFUSE proposal was turned down by DARPA, the research was carried out in subsequent NIH grants in 2018 and 2019. The model bat vaccine was created at the University of North Carolina, tested at the RML, where it successfully infected RML’s Egyptian fruit bats, and then sent from the US team to Wuhan Institute of Virology for testing in WIV’s captive horseshoe bat colony. SARS-CoV-2 accidentally leaked from the WIV during testing in the bat colony, and subsequently spread around the world, causing the COVID-19 pandemic.

This sequence of events fits a voluminous amount of otherwise inexplicable data. It is not definitively proven since the UNC, RML, and WIV have not provided full accounts of their research activities during the critical period of 2018 and 2019. Yet the evidence, both genetic and forensic, is overwhelming, enough to mandate a thorough and detailed investigation of UNC, RML, and WIV.

According to his 2018-19 documents, Ralph Baric at UNC created a SARS-like genome that triggered an immune response in mammals—he even cited the “precise molecular blueprint for SARS-CoV-2.”

Baric’s research with U.S. lab bats—Egyptian fruit bats, a non-natural reservoir host of SARS-CoV-2—provides supporting evidence.

In 2019, Vincent Munster at Rocky Mountain Lab aerosolized Baric’s genome into a transmissible vaccine, incorporating a furin cleavage site whose purpose will become evident.

A year earlier, Baric and Munster published plans to send a vaccine prototype to personnel in the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s BSL-4 for testing on Chinese bats.

Peer-reviewed studies further outline Munster’s five transmission models.

No evidence suggests a natural origin in China; no animal reservoir has been found at the Huanan wet market or anywhere else, except for Munster’s BSL-4 facility.

Shi Zhengli of the Wuhan Institute of Virology shared RaTG13 before its publication but acted as a whistleblower by republishing it on January 24, 2020. Days later, after Kristian Andersen told Jeremy Farrar he wanted to contact the FBI, Baric verbally “attacked” Andersen.

Funding for EcoHealth’s failed DARPA Defuse bid flowed through 2018-19 NIAID grants.

Baric knew the COVID-19 vaccine antidote but withheld it; Munster downplayed aerosol transmission despite housing all five mammalian models in his lab.

Priority for investigation.

Part 1: Sequence of events

If a virus is engineered, its spillover location—such as Wuhan—does not indicate where it was engineered, whether through in vivo transmission work at Rocky Mountain Lab or in vitro genomic research at the University of North Carolina (UNC). In 2018, UNC was one of several vendors that proposed to “inoculate bats” against SARS-like viruses.1 Because of their novelty, bats and their viruses were exempt from gain-of-function oversight.

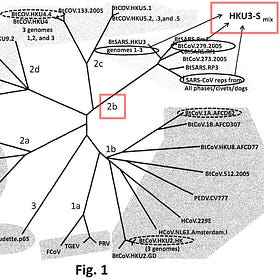

In March 2018, Professor Ralph Baric of UNC proposed a novel chimera to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Baric’s notes describe his unpublished chimera as being 20% different from SARS-CoV-1, matching the divergence of SARS-CoV-2.2 This chimera, referred to as HKU3-Smix in the DARPA Defuse proposal, indicates the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 genome.3

In 2013, Shi Zhengli of the Wuhan Institute of Virology traced the origins of SARS-CoV-1 to Chinese horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus sinicus).4 Shi also shared an unpublished bat sample, SCH014, with Baric. While Shi couldn’t isolate the virus, Baric used his reverse genetic system to recreate the genome at UNC.5 In 2015, Baric added Shi as a co-author to their Nature paper for sharing the genome before publication.6 Both insisted there was no transfer of technology or knowledge—only samples.7

In 2015, Baric patented the HKU3-Smix genome, describing it as a triple chimera that combines components from HKU3 spike, SARS-CoV receptor binding domain, and BtCoV 279 spike—details that align with his DARPA Defuse proposal. Baric’s patented chimera “provides a method of producing an immune response to a coronavirus in a subject.”8

According to the DARPA Defuse proposal, Baric planned to test the HKU3-Smix chimera on Chinese bats at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.9 The 2018 proposal named Duke-NUS Assistant Professor Danielle Anderson to “lead the animal studies” on “wild-caught” bats. She would use HKU3-Smix for infection research in Chinese horseshoe bats.

Part 2: Surrogate lab bats

Before testing Old World bats, Baric planned to test his chimera on New World bats. One issue: “I have no bat colony,” he emailed in March 2018. “No way for me to do the [bat infection] experiment—which I definitely think needs to be done, or we have no credibility. My understanding [is] another bat colony exists in China.” His Defuse bid proposed using Mexican free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis) as “proxies.” SARS-CoV-2 infects this North American species but does not transmit efficiently.10

The $14 million DARPA Defuse transferable vaccine was safe but expensive. It relied on a non-transmissible technology that required expensive field application in remote bat caves. In May 2018, DARPA rejected the bid, partly due to its 50% higher cost than competing transmissible technologies—also known as self-disseminating, contagious, self-spreading vaccines.11 Due to their novelty, transmissible animal vaccines are exempt from gain-of-function oversight.

DARPA’s program manager testified that National Institutes of Health (NIH) personnel participated in the 2018 review of these novel vaccines.12 Between 2015 and 2020, the NIH funded multiple studies on self-disseminating vaccines.132 Vincent Munster’s Rocky Mountain Lab in Montana, an original vendor on the DARPA Defuse proposal,124 had won two out of five DARPA projects with scalable, transmissible vaccine technology.13

In Defuse, Baric proposed infecting live Chinese bats with the WIV1 genome, but plans were advancing, except in Montana. In December 2018, after the DARPA Defuse bid was rejected, Baric and Munster co-published a study using Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) and the WIV1 genome—one of Baric’s favorites—but failed to achieve infection. They concluded that overcoming the ACE2 species barrier required “intracellular proteases” or a furin cleavage site.14 Mammalian bat cells also contain furin-like enzymes.15

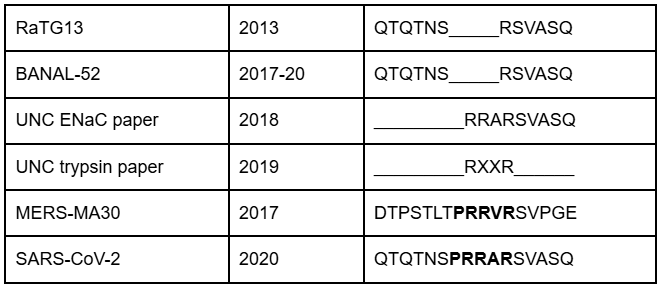

In Defuse, Baric proposed inserting a furin cleavage site (FCS) at the S1/S2 border of a novel sarbecovirus—a feature only found in SARS-CoV-2. In 2018, UNC characterized the SARS-CoV-2 FCS sequence (RRAR/SVAS) during ENaC research.16 In March 2018, Baric received Institutional Biosafety Committee (IBC) approval for ENaC experiments in human airway epithelial cells.17

QTQTNS_____RSVASQ (RaTG13)

QTQTNSPRRARSVASQ (2018 UNC ENaC research; found in SARS2)

QTQTNS_____RSVASQ (Laos Banal-52)

Shi collected RaTG13 in 2013 with funding from the NIH.111 Although unpublished in 2018, RaTG13’s unique R/SVAS region appeared in UNC’s ENaC research, suggesting prior access.18 RaTG13 was part of Baric’s 2015 quest to find a coronavirus spike protein with 25% divergence from SARS-CoV-1—RaTG13 fits this criterion.19 In Defuse, Baric aimed to create a consensus sequence within 5% divergence from RaTG13; SARS-CoV-2 is 3.9% different.20

Like RaTG13, researchers collected the BANAL-like samples before the pandemic. In 2017, the U.S. military funded a horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus) collection program in Laos, but the results were never published.21 After the pandemic—without U.S. funding—the same Laos team collected bats from the same GPS coordinates. In 2022, Institut Pasteur published the results, revealing Laos BANAL-52, which shares 96.8% genomic similarity with SARS-CoV-2 or 3.2% difference.22

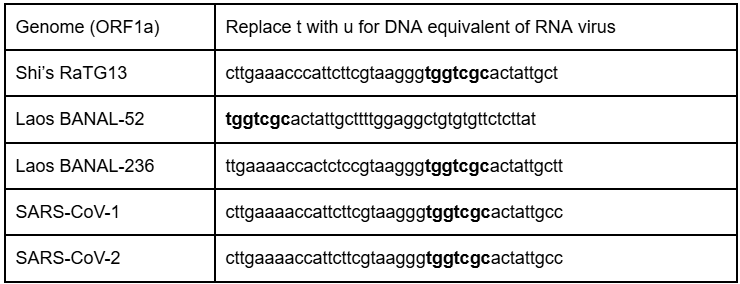

In other words, the closest progenitor to SARS-CoV-2 was collected by the U.S. military in 2017. By October 2018, Baric published a Nature paper on a live attenuated bat vaccine, referencing the Mojiang mineshaft where the RaTG13 sample originated. He described a “unique sequence motif” (UGGUCGC) to prevent recombination. This motif (CRG7) appears near the start of the open reading frame (ORF1a) in RaTG13, BANAL-52, and SARS-CoV-2.23

In late 2019, Baric published research describing an RXXR furin cleavage site.24 His paper referenced a 2017 MERS-MA30 infectious clone, described as a “precise molecular blueprint for SARS-CoV-2.”25 Notably, the SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage site has sequences from MERS-MA30, suggesting genetic engineering.

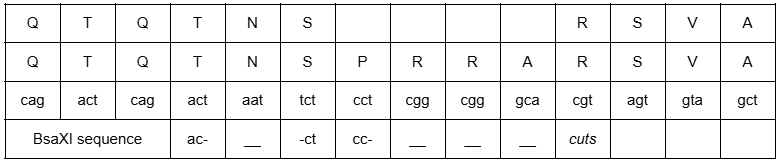

The SARS-CoV-2 genome has a specific 12-nucleotide insert at the junction of the spike protein’s S1/S2 subunits. This insert has the sequence T-CCT-CGG-CGG-GC. The CCT sequence codes for proline (P), while the two CGG sequences code for two arginine (R), and the GC starts a GCA codon, which codes for alanine (A).

An unusual BsaXI restriction site brackets the distinctive furin cleavage site (PRRA). In 2017, Baric provided details on this type IIS restriction site. Due to BsaXI’s sequence requirements, this restriction site dictated the proline (P) insertion and the double CGG-CGG codon sequence.26

In February 2019, Baric received approval from the IBC to send genomes to the Rocky Mountain Lab.27 Baric and Munster had previously used Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus) as proxies, leading them to conclude in late 2018, “It would be interesting to perform an experimental inoculation study using Chinese horseshoe bats... to investigate if more efficient virus replication and shedding can be observed.”14

In a February 2020 U.S. Capitol presentation, Baric foreshadowed, “There could be reservoir species in the U.S. that have good matches for ACE2 receptors. So, if the virus comes here, we could have an animal reservoir that the Chinese don’t. And then it hangs around for a long time.” He anticipated that this Old World virus would find a New World home.28

Part 3: Peer-reviewed in vivo evidence

Several peer-reviewed papers provide evidence for both a Wuhan lab leak and a U.S. lab origin of SARS-CoV-2. This evidence falls into two categories: genomic (in vitro) and transmission (in vivo). When investigating the origins of a novel virus, its genome alone does not reveal its entire history. However, by examining how the virus transmits and evolves in different species, researchers can gain insights into its natural origins or laboratory history.

The European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) documented, “Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was successfully demonstrated in [American] deer mice, Egyptian fruit bats and [North American] white-tailed deer… For all other animal species, transmission was not investigated.”29

If a genome is engineered in one lab but released in another, the virus will naturally seek its optimal host. During the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, the virus effectively “investigated” each species it encountered by testing compatibility with its ACE2 receptors. This revealed its transmissibility across a limited range of hosts. In short, while COVID-19 infected many species, it spread efficiently in only a few.

The ECDC continued, “The criterion used to classify the animal species of concern for SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology was the ability to shed infectious virus and to transmit SARS-CoV-2 to other individuals. The species assessed were American mink (Neogale vison), raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides), cat (Felis catus), Syrian hamster (Mesocricetus auratus), ferret (Mustela furo), house mouse (Mus musculus, for some virus variants only), Egyptian fruit bat (Rousettus aegyptiacus), deer mouse species (Peromyscus spp., not present in Europe), and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus).”

Part 4: New World vs Old World Animals

If SARS-CoV-2 had originated in the Wuhan wet market, its mammalian counterparts in the Old World would have facilitated its spread. However, the ECDC reported no SARS-CoV-2 sequences from raccoon dogs were uploaded to genomic databases. Based on genomic analysis, they concluded that infected humans most likely transmitted the virus to cats, ferrets, and several hamster species, with minimal risk of spillback to humans and little or no animal-to-animal transmission. Lab and house mice were only involved with later virus variants.

The early variants of SARS-CoV-2 were tested in multiple international labs, exemplifying a division of labor and knowledge reminiscent of SAGO’s collaborative principles. Each lab, acting in its own self-interest, contributed to the collective understanding of the virus. The selfish gene motivates both man and his engineered genome.

Out of 5,000 mammalian species, only five demonstrated efficient transmission of the virus:

Germany’s Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut (FLI) published in The Lancet: “Our data suggest that intranasal infection of Rousettus aegyptiacus bats could reflect reservoir host status and therefore represent a useful model, although this species is certainly not the original reservoir of SARS-CoV-2 because these bats are not present in China, the epicentre of the pandemic.”30

Hong Kong University published in Nature: “Notably, SARS-CoV-2 transmitted efficiently from inoculated hamsters to naïve hamsters by direct contact and via aerosols.”31

Dutch researchers documented in Eurosurveillance: “SARS-CoV-2 infection in farmed minks, the Netherlands, April and May 2020.”32

Canadian researchers published in Nature: “SARS-CoV-2 infection and transmission in the North American deer mouse.”33

Kansas State University published in Emerging Microbes & Infections: “Our results demonstrate that adult [North American white-tailed] deer are highly susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection,” and “we observed efficient transmission of virus to co-housed naïve adult deer.”34

None of the aforementioned species are native to China; however, all are maintained in U.S. laboratories. The introduction of the Old World virus, SARS-CoV-2, into New World lab animals, suggests a potential link to U.S. research activities. This pattern becomes more evident when considering that these species have served as surrogates in developing transmissible animal vaccines over the past decade.

Part 5: Transmissible bat vaccines

DARPA, NIH, and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) funded several initiatives for bat vaccines. NIAID’s research on transmissible vaccines was based at the Rocky Mountain Lab in Montana. The live bat research has been ongoing for over a decade.

In 2013, NIAID Director Tony Fauci organized a meeting with Vincent Munster of Rocky Mountain Lab and Ralph Baric of UNC. Baric proposed using Munster’s New World lab bats as “surrogates” to test his Old-World genomes.35

In 2015, NIAID’s program manager, Erik Stemmy, emailed Munster and Baric about using American mink as a coronavirus model.36

In 2017, Fauci’s biodefense presentation cited SARS-CoV-1 as a priority pathogen.128

In 2018, NIAID’s Rocky Mountain Lab won two DARPA projects on transmissible vaccines, using deer mice, Syrian hamsters, and Rousettus aegyptiacus as models.13 38

In 2018, a DARPA researcher presented deer mice, hamsters, and (Egyptian) fruit bats as transmissible vaccine models.

In 2019, Schreiner et al. discussed the timing of transmissible vaccinations for fruit bats (e.g., Rousettus aegyptiacus) and white-tailed deer.37

By 2020, NIAID had established a Rousettus aegyptiacus bat breeding colony.49

In 2020, Nuismer et al. modeled self-spreading vaccines using American deer mice housed at the Rocky Mountain Lab BSL-4.38

In 2020, the NIAID U01AI153420 grant to EcoHealth Alliance relates to the vaccination of Rousettus aegyptiacus and a transmission study involving Syrian hamsters at the Rocky Mountain Lab BSL-4.39

In 2022, Munster updated the WHO on his bat vaccine for African bats (e.g., Rousettus aegyptiacus) and African diseases (e.g., MERS, Marburg).40

The global goal was to vaccinate the reservoir species: bats—the only flying mammals. In 2019, a U.S. lab likely shipped a sample of SARS-CoV-2 to a lab in Wuhan for testing on Chinese bats. In January 2020, several travelers from Wuhan carried that sample abroad. Below is a list of travelers whose genomic samples matched those from the Wuhan wet market:

On January 20, 2020, Europe’s first diagnosed case involved a Shanghai woman visiting her company’s headquarters in Bavaria, Germany. She contracted the virus in Shanghai after her parents visited from Wuhan. On January 27, she transmitted the virus to a German man, whose viral genome, “BavPat1,” was isolated on January 28. BavPat1 was used as a “reservoir host” in Rousettus aegyptiacus.41

On January 22, 2020, a Hong Kong hospital isolated a sample (VM20001061/2020) from an adult male traveler returning from Wuhan. This sample was used as a transmission model in Syrian golden hamsters.42

On April 19, 2020, Dutch farmers reported an outbreak of respiratory disease in their American mink. Dutch scientists wrote in Eurosurveillance: “Sequence analysis of mink-derived viruses pointed at humans as the probable source of the initial infection and demonstrated transmission between minks.” Since mink (Neogale vison, formerly Neovison vison) are atypical lab animals and not native to China, this spillback required a lengthy “investigation” by the novel genome.32

On January 23, 2020, a Canadian hospital isolated a sequence (VIDO-01/2020) from an adult male hospitalized in Toronto after returning from Wuhan. This isolate was used as a transmission model in American deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus).43

On January 19, 2020, an American hospital isolated a sequence (WA1) from an adult male returning from Wuhan.44 This American man never visited the Wuhan wet market, but acquired the best-known ancestral strain of SARS-CoV-2.45

American researchers used the Seattle, Washington area strain (WA1) for transmission tests in various species. The oldest strain of SAR2-CoV-2 was “collected” by a Wuhan traveler but isolated in America. That ancestral strain from Wuhan transmits efficiently in five North American (lab) animals.

The WA1 strain (or proCoV2116) predates Lineages A and B from the Wuhan wet market.46 Therefore, WA1 contains biological evidence of a Wuhan-area lab leak and a U.S.-area lab origin. The supporting evidence for this conclusion is described below.

The United States Centers for Disease Control (US CDC) manages one of the world’s three known colonies of Rousettus aegyptiacus. In 2024, a US CDC employee confirmed their colony was a “non-natural” host for WA1.47 Besides the US CDC and FLI in Germany, the third known colony is maintained at Colorado State University (CSU).48 In February 2020, Tony Schountz of CSU infected their colony with WA1. By April 2020, Schountz informed Munster that the bats exhibited reservoir host characteristics—efficient transmission without symptoms.49 Schountz bred this colony for Munster’s DARPA PREEMPT project, which aimed to develop a transmissible bat vaccine.50

Rocky Mountain Lab used the WA1 sequence in a successful Syrian hamster transmission experiment. However, the Nature publication was published four years after the pandemic, and they combined the WA1 sequence with the Delta variant.51

Rocky Mountain Lab used the WA1 sequence in a successful American mink transmission experiment. However, they mixed the sequence with the B.1.1.7 variants.52

Colorado State University used the WA1 sequence in a successful deer mice transmission experiment. Their PLOS Pathogens paper was aptly titled, “SARS-CoV-2 infection, neuropathogenesis, and transmission among deer mice: Implications for spillback to New World rodents.”53

Kansas State University used the WA1 sequence in a successful white-tailed deer transmission experiment. However, they combined the ancestral sequence with the Alpha variants.34

Part 6: No Chinese animal reservoirs

Ancestral SARS-CoV-2 transmitted in only five species: U.S. lab bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus), Syrian golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus), American mink (Neogale vison), American deer mice (Peromyscus maniculatus), and North American white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus).

None are native to China, but four appear in U.S. self-spreading vaccine research.

Rocky Mountain Lab proposed Rousettus aegyptiacus (Egyptian fruit) bats as a DARPA PREEMPT transmission model.54

No one has documented Syrian hamsters at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, but the Rocky Mountain Lab proposed them as a DARPA PREEMPT transmission model.54

American mink are not found in China, but they are kept at the Rocky Mountain Lab.55

American deer mice are modeled for self-spreading animal vaccines in the Rocky Mountain BSL-4.38

American deer are kept in U.S. labs and proposed as models for self-disseminating vaccines.5657

This suggests that SARS-CoV-2 was likely serially passaged in these five species, which are found exclusively at the Rocky Mountain Lab facility.

Part 7: The quiet whistleblowers

The SARS-CoV-2 genome was uploaded on January 10, 2020. Munster emailed Baric, stating, “Perfect, right between your favorite viruses :-)”58 We believe that Baric’s patented HKU3-Smix genome had been renamed SARS-CoV-2. It differed by 20% from SARS-CoV-1, placing it between HKU3 (~30%) and WIV1 or SHC014 (~10%)—Baric’s most researched genomes.

On the same day, Professor Linfa Wang of Duke-NUS resigned as director of Emerging Infectious Diseases.59 His subordinate, Danielle Anderson, had worked at the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s BSL-4 until November 2019.60 Twenty miles north of Danielle Anderson’s BSL-4 is Shi Zhengli’s BSL-2, where Shi uploaded the RaTG13 genome on January 24, 2020, to GISAID and on January 27 to NCBI.61 Until then, no one suspected SARS-CoV-2 was engineered.

A week later, Professor Kristian Andersen of the Scripps Institute considered contacting the FBI and CIA.62 He aligned RaTG13 with SARS-CoV-2 and found a 100% match at the S1/S2 region, except for the furin cleavage site (PRRAR), which was inserted out of frame—an anomaly suggestive of manmade manipulation.

YECDIPIGAGICASYQTQTNS_____RSVASQSIIAYTMSLGAENSVAYSNN (RaTG13)

YECDIPIGAGICASYQTQTNSPRRARSVASQSIIAYTMSLGAENSVAYSNN (SARS2)

In his book Spike, Dr. Jeremy Farrar of the Wellcome Trust documented Andersen’s desire to contact the FBI on January 30, 2020. The next day, Farrar urged Tony Fauci to call Andersen, which he did. However, Andersen testified that Fauci intended to inform the FBI.63

After their Friday night phone call on January 31, Andersen emailed Fauci to document that we “all find the genome inconsistent with expectations from evolutionary theory.” The royal “we” referred to the elite of evolutionary virology: Andersen, Robert Garry, Andrew Rambaut, and Eddie Holmes. Fauci replied, “Thanks, Kristian. Talk soon on the call.”64

The following Saturday, February 1, Farrar convened a teleconference with Fauci, who invited NIH Director Francis Collins and Deputy Director Lawrence Tabak. Fauci did not invite the FBI, and Farrar excluded Ralph Baric. Farrar shared Andersen’s PowerPoint slides with an international group of virologists, doctors, professors, and directors.

Andersen’s presentation highlighted the furin cleavage site (PRRAR) as an engineered anomaly. He aligned the SARS-CoV-2 genome with Shi’s new bat coronavirus, RaTG13. One of his six slides focused on the spike protein’s S1/S2 border.65

QTQTNS_____RSVASQ (RaTG13 uploaded Jan 24)

QTQTNSPRRARSVASQ (SARS2 uploaded Jan 10)

In an email to Fauci and others, Professor Robert Garry of Tulane wrote, “Do the alignment of the spikes at the amino acid level—it’s stunning.” Garry noted that the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is identical to RaTG13 bat coronavirus, except for a perfect 12-nucleotide furin cleavage site insertion at the S1/S2 border, which he found implausible through natural evolution but achievable in a lab.65

Professor Andrew Rambaut of the University of Edinburgh added, “RaTG13 is identical except for the four residue insertions.”65 Professor Eddie Holmes, an evolutionary virologist from the University of Australia, emailed, “Things were made worse when [Shi] published [the RaTG13] sequence.”65 He later questioned why Shi would publish RaTG13 if her lab was the source of the outbreak.66

Recent testimony from participants during the February 1, 2020, teleconference sheds new light on what happened next. One ghost participant, never disclosed, was Ralph Baric. Four years later, in January 2024, he testified that Fauci invited him to listen in—but he never announced his presence to the evolutionary virologists.68

Baric testified that the February 1 teleconference “was heavily dominated by evolutionary biologists, who were split on the origin of the virus.” He listened quietly to the genetic engineering evidence presented by Andersen, Garry, Rambaut, and Holmes. However, Baric would soon dominate the debate.

Two days later, at a follow-up meeting on February 3, Fauci convened White House officials, the FBI, ODNI, NASEM, and other U.S. government agencies.99 Andersen was again asked to provide his evidence for engineering. In front of everyone, Baric “attacked” Andersen and dismissed his lab leak theory as “ludicrous” and full of “crackpot theories.”68

Andersen testified in 2023, “Ralph Baric, for example, is a name that came up. We all know Ralph. Ralph is a very important coronavirus biologist. But we also knew that Ralph had very close associations and collaborations with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, for example. So if this did, in fact, originate from a lab, then, of course, he would not be a person to have on a [February 1] call like this.”62

In 2024, Andersen admitted he had “no idea” that Baric was on the call from February 1, 2020.67 In a redacted February 3, 2020, Slack message revealed in Baric’s testimony, Andersen wrote, “I should mention that Ralph Baric pretty much attacked me on the call with NASEM, essentially calling anything related to potential lab escape ludicrous, crackpot theories. I wonder if he, himself, is worried about this, too.”68

Part 8: Funding

Baric had reason to be worried. Two years earlier, he had proposed to “introduce” furin cleavage sites into bat samples like RaTG13.3 Later, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Murphy, a DARPA fellow, leaked the DARPA Defuse proposal, stating, “SARS-CoV-2 is an American-created recombinant bat vaccine.” Murphy added, “As is known, Dr. Fauci with NIAID did not reject the proposal.”69

A U.S. Senator asked Fauci if this was true, and he replied, “We have never seen ‘that’ grant and we have not funded ‘that’ grant.”70 This was because Peter Daszak of EcoHealth split the $14 million DARPA Defuse bid into two NIAID grants, effectively concealing its origins.47 However, Fauci’s Rocky Mountain Lab was an original vendor on the DARPA Defuse bid.124

In May 2018, DARPA rejected Baric’s gain-of-function proposal, citing concerns over dual-use research. By October 2018, Daszak added Baric to Shi’s 2R01AI110964 grant, and by 2019, the grant mirrored Technical Area 1 of the DARPA Defuse proposal—same scope, same personnel, same human airway epithelial (HAE) cells.71

Shi used Vero cells that deleted the furin cleavage site, while Baric used HAE.72 In theory, Baric could have advised labs worldwide to passage the virus on Vero cells, removing the furin cleavage site and turning the contagious animal vaccine into an attenuated human vaccine.73 Instead, he remained silent for four years and provided conflicting testimony.

Baric testified that Shi used baculovirus technology, which left a “sequence signature” based on the WIV1 molecular clone (closer to SARS1 than SARS2). Baric continued, “We think our [UNC] approach is safer because we've divided the genome into six pieces,” just like SARS-CoV-2. The five type IIS restriction sites in the SARS-CoV-2 genome yield six fragments, as documented by Bruttel et al.74

Baric testified that the Bruttel et al. bioRxiv paper was a “pathetic piece of work. By the way, you can see how I engineered the SARS-CoV-2 genome since it’s published, and you will see that it’s completely different than this.”

Baric’s only alibi was his greatest confession—he could create the SARS-CoV-2 genome without modifications. His reverse genetic system aligned perfectly with what emerged in Wuhan. However, he restructured the genome, dividing it into seven fragments instead of using the existing six. He inserted a new restriction site between each of the existing ones.75 In other words, Baric apparently constructed a biological alibi in 2020 for his future testimony in 2024.

On March 5, 2020, U.S. government biodefense officials asked Baric in the Red Dawn emails whether SARS-CoV-2 contained “any restriction sites” suggesting genetic engineering. Baric responded, “No, there is absolutely no evidence of genetic engineering.”76

Baric later testified, “We didn’t publish the [2015 SHC014] sequence of the virus that we built, and we didn’t share the sequence of that chimera with anyone at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. So we didn’t give them the template on how to build the recombinant virus.” In a 2018 DARPA Defuse draft, Baric offered to send Linfa Wang of Duke-NUS his novel SHC014 chimeras to “test in captive bats.”1

On November 18, 2019, Wang, Anderson, Daszak, and Baric’s U01AI151797 CREID grant received a score of 32—worse than Robert Garry and Kristian Andersen’s score of 27. Yet, with Fauci’s backing, the U01AI151797 grant was awarded to Baric’s team despite its striking resemblance to Technical Area 2 of the Defuse proposal—including a “furin cleavage site” in Baric’s draft.77

Both of Baric’s new 2019 NIAID grants referenced a novel genome, HKU3r-CoVs, where “r” signified a bat backbone rather than a human one—Baric’s workaround of dual-use research concerns.78 Two months later, Fauci secretly invited Baric to the February 1, 2020, teleconference. What emerged in Wuhan in late 2019 had been proposed by Baric in early 2018 and funded by Fauci in 2019.

Part 9: Cover-up

On February 11, 2020, Baric met with Fauci in his office to discuss the “outbreak and chimeras.” Days later, Baric told a colleague that Shi could be “arrested” for publishing RaTG13.79 After Shi published the natural RaTG13 bat sample, evidence of genetic engineering emerged. This was the second time she had uploaded the RaTG13 genome.

Shi uploaded the 4991 bat sample as RaTG13 to the NIH database in July 2018, but RaTG13’s partial genome was embargoed until 2022.80 When Shi re-uploaded RaTG13 to GISAID after the pandemic began, she revealed the furin cleavage site. Had Shi not re-uploaded RaTG13, the messy S1/S2 alignment would have appeared as this.

YHTASI_____LRSTGQKA (ZXC21 Shanghai area bat samples published in 2018)

QTQTNSPRRARSVASQ (SARS-CoV-2 uploaded January 10, 2020)

YHTASI_____LRSTGQKA (ZC45 Shanghai area bat samples published in 2018)

Until Shi republished the RaTG13 genome, no one suspected the SARS-CoV-2 genome was engineered. There was nothing comparable. Shi had shared unpublished bat samples, such as SHC014, with Baric before publication. Like SHC014, Shi couldn’t isolate RaTG13, but Baric could reconstruct the virus from the genetic sequence she uploaded.81

In 2024 testimony, Baric was asked, “Shi Zhengli went back to her holdings and found RaTG13. I don’t know if you did a similar one just to see if you had something similar.” He dodged the question twice, stating, “I don’t do surveillance.” In the 2R01AI110964 grant, Shi does Baric’s surveillance. To this day, Baric has never disclosed the contents of his UNC freezer.

Baric was questioned about his 2019 addition to the 2R01AI110964 grant, which focused on genomes with a 10% to 25% divergence from SARS-CoV-1. He testified, “WIV1 and SHC014 show 8% to 12% variation in the spike... HKU3 strains show 30% to 35% variation... If you subtract 10-12 from 35, divide by 2, and add to 12, you get 20-25%. SARS-CoV-2 [spike] had a 22% variation, so we were within range but not completely right.”

Baric was right, indicating he had a genome within 2% range of SARS-CoV-2, which is closer than Shi’s RaTG13. If a virus is engineered, the location of its spillover—such as Wuhan—does not indicate where it was engineered—like North Carolina. NIAID references Material Transfer Agreements (MTAs) in their 2R01AI110964 grant, while U01AI151797 referenced the “cold chain”—with thousands of dollars allocated for shipping frozen bat samples in liquid nitrogen.82

After SARS-CoV-2 emerged in Wuhan and Baric verbally attacked Andersen, Andersen’s one-page lab leak report from February 1, 2020, evolved into the Nature paper “The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2.”83

Andersen’s co-authors made a key revision to footnote number 20 by swapping the citation from Baric’s 2015 Nature paper to an irrelevant 2014 Spanish lab paper, stating, “The genetic data irrefutably shows that SARS-CoV-2 is not derived from any previously used virus backbone.”84

The Proximal Origin co-authors ignored Baric’s 2017 reverse genetic system, which used Type IIS restriction sites—just like SARS-CoV-2.85 Baric’s “No See’m” technique created “candidate vaccine strains” to conceal the genetic manipulation from a Chinese bat’s immune system—not lab-leak researchers.86 If Baric’s genome were to leak from a Wuhan lab, it would appear to originate from a Wuhan wet market.

In a February 26, 2020, presentation to Congressional staffers, Baric discussed the Wuhan wet market but did not mention the SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage site. He did not disclose his DARPA Defuse document or plans to “introduce” furin cleavage sites in viruses like SARS-CoV-2.28

Major Murphy leaked the DARPA Defuse document and stated, “The asymptomatic nature is also explained by the bat vaccine intention of its creators—a good vaccine does not generate symptoms.”69 Self-spreading vaccines evade immunity to enhance spread.131

Bats hold unique relevance because, unlike birds, they are mammals with a closer physiology to humans.87 Baric had long studied mammalian immune evasion, supported by his research and patents.88 The final Defuse proposal outlined that “Prof. Baric (UNC) will lead the targeted immune boosting work,” extending to “small groups of wild-caught Rhinolophus sinicus bats at WIV.”3

Wuhan possessed something that North Carolina and Montana lacked: live Chinese horseshoe bats, the reservoir for SARS-CoV-1, which disrupted 2003 U.S. military operations in Asia. As Baric noted, “About 90,000 of the 550,000 deployed U.S. military personnel” are in Southeast Asia.1 His ambitious idea was to vaccinate the bats to prevent the next spillover event. Everyone was doing it—including Fauci.

On January 8, 2020, Fauci edited a Nipah bat vaccine paper—the only non-HIV paper he has ever edited.89 The EcoHealth paper, funded by his NIAID grant (U01AI153420), aimed to vaccinate Asian bats using the Rousettus aegyptiacus model and included Syrian hamsters at the Rocky Mountain Lab—two of the five SARS-CoV-2 transmission models.39

Unlike raccoon dogs and humanized mice, which require intranasal inoculation with 100,000 infectious particles, Syrian hamsters need only 5 particles for transmission.90 While raccoon dogs and humanized mice are native to Wuhan, Syrian hamsters are not found in Wuhan labs.91 Syrian hamsters have been transmission models at Rocky Mountain Lab since 2011.92

On January 27, 2020, Munster presented Fauci with a detailed SARS-CoV-2 presentation.93 By March, they exchanged emails but downplayed aerosol transmission.64 Munster’s NEJM paper labeled aerosol transmission as “plausible,” despite all five transmission models in his lab.94

Fauci dismissed reports of the virus traveling 27 feet as “terribly misleading,” claiming only an exaggerated sneeze could reach such a distance.95 However, SARS-CoV-2 can travel up to 60 feet—ten times the 6-foot distancing guideline.96

On February 7, 2020, Daszak invited Munster to sign the Lancet letter, but he declined.97 The letter condemned lab leak “conspiracy theories.”98 Although Baric was cited three times, Daszak, after consulting Linfa Wang, advised him not to sign it to avoid drawing attention to their “collaboration.” Baric agreed, calling it a “good decision” since his signature would appear “self-serving” and reduce the letter’s “impact.”99

Baric’s signature is likely found in the SARS-CoV-2 genome, while the airborne agent can likely be traced back to Munster’s lab. The pandemic’s impact, along with the subsequent efforts to obscure its origins, likely traces back to the actions of these two individuals. These two seem to have misled or concealed crucial information, whether by omission or commission, indicating a deliberate attempt to hide their responsibility for the worst pandemic in history.

Part 10: Priority for investigation

Peter Daszak’s DARPA Defuse document was rejected in May 2018, but Technical Areas One and Two were reissued in the 2R01AI110964 and U01AI151797 NIAID grants.100 On November 18, 2019, Daszak listed Fauci as “key people... making the [U01] decision.”77 We would like to see Daszak’s 2018-19 emails with NIAID staff, Danielle Anderson, Linfa Wang, Ralph Baric, and Vincent Munster.

Daszak’s first words to Lancet Commissioner Jeffrey Sachs were a denial: there were no bats in the Wuhan lab. However, on May 18, 2024, Daszak posted on X, “The real irony of this is that the 1st credible info I got about a bat colony was later on when I led the Lancet Origins probe & Dani Anderson confirmed it. We managed to get WIV to confirm also. This was supposed to be made public in our report but Sachs closed us down.”101

Danielle Anderson edited DARPA Defuse Technical Area Two in June 2019 while applying for Daszak’s U01AI151797 NIAID grant.102 She entered the Wuhan BSL-4 facility around July and left in November 2019.103 Although she claimed to be working on Ebola, we would like to review her lab notebooks, MTAs, and emails from 2019. Additionally, she should release her 2020 COVID-19 antibody test results.104

Linfa Wang resigned as the director of Duke’s Emerging Infectious Diseases on January 10, 2020 (effective August 31, 2020).59 He has been a beacon of truth in this sordid mess, but his mobile phone was at the Wuhan BSL-4 facility in November 2019.105 We request an explanation for both dates. Wang also denied that any U.S. lab sent him an HKU3-like genome, but we want to review his MTAs and emails.47

Ralph Baric has declined to release his 2019 emails to the U.S. Right to Know, citing “proprietary” data.106 Baric’s patented HKU3-Smix and HKU3r-CoV genomes resemble SARS-CoV-2, so we are interested in examining his UNC lab records. We request Baric’s MTAs, shipping receipts, emails, lab books, and DNA sequences from the past decade.

According to a peer-reviewed paper in BMC Genomic Data, Baric referenced a “precise molecular blueprint for SARS-CoV-2.” This 2017 molecular clone, MERS-MA30, is in the SARS-CoV-2 furin cleavage site.25 Baric’s first pandemic paper did not mention the furin cleavage site.107 We want to examine all UNC molecular clones and their IBC signatures.

Baric received pre-pandemic IBC approval to create infectious clones of CRG7 and HKU3,17 27 and post-pandemic RaTG13 and Laos Banal, which need publication.108 Baric must explain why he used seven new fragments instead of the existing six fragments for his SARS-CoV-2 reverse genetic system.75 His longtime UNC postdoc, Vineet Menachery, now at UTMB-Galveston, used the same number and location of restriction sites.109 Their published results even confused the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) analysis.110

According to Kristian Andersen’s unredacted Slack messages, Baric “attacked” him on February 3, 2020, for suggesting the SARS-CoV-2 genome looks engineered. Baric reportedly then suggested that Shi could be arrested for publishing RaTG13. In January 2021, during a U.S. State Department “red team” meeting, Baric bullied a participant who presented a Bayesian analysis favoring a lab leak. Baric should explain his behavior.

On January 24, 2020, Shi uploaded RaTG13, which made her BSL-2 lab a suspect, since it was the closest known genome. The NIAID R01AI110964 grant had funded the collection of RaTG13.111 However, her molecular clone WIV1 and the isolated viruses WIV15, 4874, and WIV16 were closer to SARS-CoV-1. Post-pandemic, it was revealed that the U.S. military had collected the closest known progenitor before the outbreak.

After the pandemic, but without U.S. military funding, the Institut Pasteur recollected the same Laos BANAL bat samples.21 However, this time, they published the results. The researchers discovered antibodies produced by people during COVID-19 infection were potent against the BANAL sample.22 We request this challenge study be conducted on Egyptian fruit bats at the Rocky Mountain Lab.

Vincent Munster’s DARPA-funded postdoc at Rocky Mountain Lab, Michael Letko, recently presented his research from 2018 to 2019.112 He outlined DARPA Defuse-type research that focused on ACE2 receptors for coronaviruses. We want to review Letko’s research and lab book, as a U.S. Senator has requested the same information.113

On January 22, 2020, Letko and Munster uploaded a bioRxiv preprint, confirming that human ACE2 is the receptor for SARS-CoV-2.114 Kristian Andersen said, “It’s unbelievably fast, almost too fast to imagine.”115 We request an explanation for why the furin cleavage site was omitted.

In April 2020, Schountz of CSU reported “peculiar data” from WA1 infection tests on Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus). The U.S. lab bats tested PCR positive for three weeks and carried 10,000 infectious particles but showed no symptoms—hallmarks of a reservoir host. Not surprisingly, SARS-CoV-2 was transmitted via aerosols to three bats housed in a “separate cage ABOVE the inoculated bats.” Munster responded with, “Weird results,” but no publication followed on these findings.49 We would like those WA1 test results published.

Virologists consider WA1 the best-known “progenitor” of SARS-CoV-2.116 However, by December 2019, COVID-19 antibodies were detected in Norwegian pregnant women and West Coast U.S. blood donors.117118

Rocky Mountain Lab published a study on American mink transmission with England’s Alpha variant (B.1.1.7), not just the WA1 strain. We request the records of all mink transmission research conducted at Rocky Mountain Lab.

Rocky Mountain Lab started an American deer mouse colony in 2017.119 Colorado and Canadian labs have published transmission results, but Rocky Mountain Lab has not.120 We want the WA1 transmission study to be published.

North American white-tailed deer are now recognized as the only wildlife reservoir for SARS-CoV-2.121 An Iowa lab has published research on deer transmission, which Munster edited, but Munster has not published Rocky Mountain Lab results.122 Unlike Old World deer, New World deer possess the K31 mutation in their ACE2 receptor.123 Given these factors, we seek publication of the WA1 transmission study.

Syrian hamsters were a transmission model for DARPA PREEMPT and NIAID’s vaccine development efforts (U01AI153420). We request the records of all Syrian hamster transmission research conducted at Rocky Mountain Lab.

Rocky Mountain Lab was listed as an original vendor on the DARPA Defuse bid but was removed for unknown reasons.124 We want to review Munster’s lab books, MTAs, shipping records, emails, DNA sequences, and lab animal inventory from the past decade.

Finally, Fauci should explain why Daszak listed him as a “key” person in his November 2019 email, why he edited an EcoHealth bat vaccine paper on January 8, 2020, why he received Munster’s pandemic presentation on January 27, why he didn’t call the FBI on January 31, and why he invited Baric to the February 1 teleconference.

During his 2024 testimony, Fauci claimed credit for the idea of calling the FBI, but Farrar’s Viral documented that Andersen had wanted to contact the FBI by January 30, 2020.125 While Farrar informed MI5, Fauci arranged a February 3 NASEM meeting that included the FBI, where Baric “attacked” Andersen. Fauci then “prompted” Andersen et al. to write The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2 in Nature, shaping the early scientific narrative on COVID-19’s origins.126

On February 6, 2020, Fauci scheduled a meeting with Baric on February 11.127 On March 10, Fauci presented with Baric, who omitted the furin cleavage site’s pandemic potential.128 Fauci’s 2017 biodefense presentation set the stage for SARS-CoV-2 by listing SARS-CoV-1 as a priority pathogen.129

Despite housing all five transmission models at their Rocky Mountain Lab, Fauci and Munster downplayed asymptomatic and aerosol transmission. COVID-19 spread as designed—in the upper respiratory tract of mammals. Yet bats, bat viruses, and transmissible animal vaccines were excluded from gain-of-function guidelines after 2017, when the NIH quietly removed a broad reference to mammals.130

Self-spreading bat vaccines created incentives to evade the immune response, as any pre-existing immunity to the vaccine vector would slow the spread of the vaccine.131 Tragically, human beings became the target of this transmissible vaccine—developed with NIH funding.132 In light of recent publications,133 including from Princeton University, we urge an immediate moratorium on this risky research.134

In the end, the peer-reviewed literature revealed a bitter truth: Fauci, Baric, and Munster concealed evidence of a likely U.S. lab origin of SARS-CoV-2. Only by publishing the unpublished data and addressing the still outstanding questions can the scientific community restore credibility and rebuild public trust, and justice can be done for a pandemic that claimed millions of lives and trillions of dollars in lost income worldwide.

USGS DEFUSE full batch (1.18.24) Baric HK3 notes. Page 483 of 1417. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/USGS-DEFUSE-2021-006245-Combined-Records_Redacted.pdf

Baric interview (1.22.24) HK3 is HKU3, but 293 is a typo. Page 199 of 212. https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Baric-TI-Transcript.pdf

DARPA Defuse document (3.24.18). Page 19 of 75. https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/21066966/defuse-proposal.pdf

Ge et al. 2013. “Isolation and Characterization of a Bat SARS-like Coronavirus That Uses the ACE2 Receptor.” Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12711

Jacobsen, Rowan. 2021. “Ralph Baric Explains Gain-of-function Research.” MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/07/26/1030043/gain-of-function-research-coronavirus-ralph-baric-vaccines/

Menachery et al. 2015. “A SARS-like Cluster of Circulating Bat Coronaviruses Shows Potential for Human Emergence.” Nature Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3985

Qiu, Jane. 2022. “Meet the Scientist at the Center of the Covid Lab Leak Controversy.” MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/02/09/1044985/shi-zhengli-covid-lab-leak-wuhan/

Baric et al. 2015. “US9884895B2 - Methods and Compositions for Chimeric Coronavirus Spike Proteins.” https://patents.google.com/patent/US9884895B2/en

Wang, Linfa

Hal et al. 2023. “Experimental Infection of Mexican Free-Tailed Bats (Tadarida Brasiliensis) With SARS-CoV-2.” mSphere. https://doi.org/10.1128/msphere.00263-22

Nuismer et al. 2020. “Self-disseminating Vaccines to Suppress Zoonoses.” Nature Ecology & Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1254-y

“A New Layer of Medical Preparedness to Combat Emerging Infectious Disease.” https://www.darpa.mil/news/2019/medical-preparedness

Van Doremalen et al. 2018. “SARS-Like Coronavirus WIV1-CoV Does Not Replicate in Egyptian Fruit Bats (Rousettus Aegyptiacus).” Viruses. https://doi.org/10.3390/v10120727

Millet et al. 2014. “Host Cell Proteases.” Virus Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2014.11.021

Harrison, Sachs. 2022. “A Call for an Independent Inquiry Into the Origin of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2202769119

UNC IBC meeting minutes (Jan 2016 - Jan 2024) page 97 of 427 https://t.co/GBLYDRARjO

Quay. 2025. “The Potential Role of the University of North Carolina in SARS-CoV-2 Research: An Investigative Analysis.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15062163

Branswell. 2023. “SARS-like Virus in Bats Shows Potential to Infect Humans, Study Finds.” STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2015/11/09/sars-like-virus-bats-shows-potential-infect-humans-study-finds/

Becker et al. 2008. “Synthetic Recombinant Bat SARS-like Coronavirus Is Infectious in Cultured Cells and in Mice.” PNAS. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0808116105

Institut Pasteur Du Laos. “Assessment of the Potential Vector Threat of Bat-borne Pathogens and the Host-associated Ectoparasites in the Provinces of Vientiane and Khammouane of the Lao PDR (Bat Map Project).” https://tinyurl.com/36jfst85

Temmam et al. 2022. “Bat Coronaviruses Related to SARS-CoV-2 and Infectious for Human Cells.” Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04532-4

Graham et al. 2018. “Evaluation of a Recombination-resistant Coronavirus as a Broadly Applicable, Rapidly Implementable Vaccine Platform.” Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-018-0175-7

Menachery et al. 2019. “Trypsin Treatment Unlocks Barrier for Zoonotic Bat Coronavirus Infection.” Journal of Virology. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01774-19

Lisewski. 2024. “Pre-pandemic Artificial MERS Analog of Polyfunctional SARS-CoV-2 S1/S2 Furin Cleavage Site Domain Is Unique Among Spike Proteins of Genus Betacoronavirus.” BMC Genomic Data. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-024-01290-2

Harrison, Neil, Sachs, Jeffrey. 2023. “What Is a Furin Cleavage Site, Why Is It Important, and How Might This Have Arisen in SARS-CoV-2?” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7742605

U.S.R.T.K. Baric emails batch #9 (4.17.24) page 279 of 606 pages. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/2024.01.29-_-Response-04.16.2024.pdf

Baric. Feb 26, 2020.

“SARS-CoV-2 in Animals: Susceptibility of Animal Species, Risk for Animal and Public Health, Monitoring, Prevention and Control.” 2023. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/sars-cov-2-animals-susceptibility-animal-species-risk-animal-and-public-health.

Schlottau et al. 2020. “SARS-CoV-2 in Fruit Bats, Ferrets, Pigs, and Chickens: An Experimental Transmission Study.” The Lancet Microbe. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2666-5247(20)30089-6

Sia et al. 2020. “Pathogenesis and Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Golden Hamsters.” Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2342-5

Oreshkova et al. 2020. “SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Farmed Minks, the Netherlands, April and May 2020.” Eurosurveillance. https://doi.org/10.2807/1560-7917.es.2020.25.23.2001005

Griffin et al. 2021. “SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Transmission in the North American Deer Mouse.” Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-23848-9

Cool et al. 2021. “Infection and Transmission of Ancestral SARS-CoV-2 and Its Alpha Variant in Pregnant White-tailed Deer.” Emerging Microbes & Infections. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2021.2012528

Fauci, Baric, Munster. MERS. 2013. 3:31:00 timestamp. https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=12908

U.S.R.T.K. NIH batch #38 (9.5.24) Stemmy mink email on Oct 2, 2015—page 297 of 302. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/USRTK-Prod-3-03.11.24.doj-nih.pdf

Schreiner et al. 2019. “When to Vaccinate a Fluctuating Wildlife Population: Is Timing Everything?” Journal of Applied Ecology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13539

Nuismer et al. 2020. “Bayesian Estimation of Lassa Virus Epidemiological Parameters: Implications for Spillover Prevention Using Wildlife Vaccination.” PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0007920

U.S.R.T.K. NIH batch #74 (1.30.25) U01AI153420 grant on page 222 of 500. https://files.usrtk.org/NIH-FOIA-Request-55569-November-Production_Redacted.pdf

Munster. WHO. 2022. 44:00 timestamp.

Böhmer et al. 2020. “Investigation of a COVID-19 Outbreak in Germany Resulting From a Single Travel-associated Primary Case: A Case Series.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30314-5

BEI Reagent Search. https://www.beiresources.org/Catalog/animalviruses/NR-52282.aspx

Marchand-Senécal et al. 2020. “Diagnosis and Management of First Case of COVID-19 in Canada: Lessons Applied From SARS-CoV-1.” Clinical Infectious Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa227

Holshue et al. 2020. “First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States.” New England Journal of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2001191

Worobey et al. 2020. “The Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in Europe and North America.” Science. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc8169

Kumar et al. 2021. “An Evolutionary Portrait of the Progenitor SARS-CoV-2 and Its Dominant Offshoots in COVID-19 Pandemic.” Molecular Biology and Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab118

Haslam, Jim. COVID-19: Mystery Solved. Chapter 29.

U.S.R.T.K. CSU batch Schountz (1.21.21) DARPA PREEMPT project. Page 2190 of 2276. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/CSU_records.pdf

U.S.R.T.K. NIH batch #61 (10.7.24) Schountz Rousettus bat email. Page 20 & 392 of 520. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/NIH-FOIA-Request-56077-March-Production_Redacted.pdf

Suryanarayanan 2021. “Colorado State University Documents on Bat Pathogen Research.” U.S.R.T.K. Hamsters and fruit bats as DARPA PREEMPT transmission models. https://usrtk.org/covid-19-origins/colorado-state-university-documents-on-bat-pathogen-research/

Yinda et al. 2024. “Airborne Transmission Efficiency of SARS-CoV-2 in Syrian Hamsters Is Not Influenced by Environmental Conditions.” Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44298-023-00011-3

Adney et al. 2022. “Severe Acute Respiratory Disease in American Mink Experimentally Infected With SARS-CoV-2.” JCI Insight. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.159573

Fagre et al. 2021. “SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Neuropathogenesis and Transmission Among Deer Mice: Implications for Spillback to New World Rodents.” PLoS Pathogens. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1009585

U.S.R.T.K. NIH batch #56 (9.5.24). Munster Rousettus DARPA slides on page 224 of 501. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/NIH-FOIA-Request-56077-and-56301-May-Production_Redacted.pdf

Harrington et al. 2021. “Wild American Mink (Neovison Vison) May Pose a COVID‐19 Threat.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2344

Palmer et al. 2017. “Using White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus Virginianus) in Infectious Disease Research.” https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5517323/

Palmer et al. 2018. “Use of the Human Vaccine, Mycobacterium Bovis Bacillus Calmette Guérin in Deer.” Frontiers in Veterinary Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2018.00244

U.S.R.T.K. NIH batch #65 (10.8.24) page 224 of 500 pages. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/NIH-FOIA-Request-56077-April-Production_Redacted.pdf

Cortez. 2021. “The Last—And Only—Foreign Scientist in the Wuhan Lab Speaks Out.” Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-06-27/did-covid-come-from-a-lab-scientist-at-wuhan-institute-speaks-out

January 27, 2020. RaTG13 genome https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MN996532.1

Andersen interview. Page 92 of 209. https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2023.06.16-Andersen-Transcript.pdf

Andersen Congressional hearing.

Fauci FOIA page 3187 of 3234. https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/20793561/leopold-nih-foia-anthony-fauci-emails.pdf

FOIA page 59, 107 & 131 of 174. https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/23316400-farrar-fauci-comms/

Slack page 131 of 140. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Proximal_Origin_Slack_OCRd.pdf

Andersen. 2024. Medium blog post reply. https://medium.com/@K_G_Andersen/its-not-about-getting-the-scoop-it-s-about-getting-it-right-origin-of-covid-19-my-emails-7447e59d79e3

Baric interview (1.22.24) page 120 of 212. https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Baric-TI-Transcript.pdf

Fauci hearing. Jan 11, 2022.

Intercept FOIA of 2R01AI110964 in September 2021. https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/21055989/understanding-risk-bat-coronavirus-emergence-grant-notice.pdf

Hu et al. 2017. “Discovery of a Rich Gene Pool of Bat SARS-related Coronaviruses Provides New Insights Into the Origin of SARS Coronavirus.” PLoS. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006698

Adler et al. 2023. “A Non-transmissible Live Attenuated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine.” Molecular Therapy.. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.05.004

Bruttel et al. 2022. “Endonuclease Fingerprint Indicates a Synthetic Origin of SARS-CoV-2.” bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.10.18.512756

Hou et al. 2020. “SARS-CoV-2 Reverse Genetics Reveals a Variable Infection Gradient in the Respiratory Tract.” Cell. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.042

Red Dawn emails page 61 of 81. https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/6879-2020-covid-19-red-dawn-rising/66f590d5cd41e11bea0f/optimized/full.pdf

U.S.R.T.K. DoD USU batch #4 (7.8.24). Page 1110 & 1659 of 1967 pages. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Q1-Broder-3rd-round-combined.pdf

U.S.R.T.K. March 2018 Baric email. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/EHA_Epstein_2018_Baric-Files.pdf

U.S.R.T.K. Slack message page 283 of 1611. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/ED-20-01981-F-Dec-2022-Production-OPAQUE.pdf

RaTG13 partial upload in 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MH615843

Shi’s RaTG13 reply to Science Magazine. https://www.science.org/pb-assets/PDF/News%20PDFs/Shi%20Zhengli%20Q&A-1630433861.pdf

Baric statement on NIH MTAs. https://www.scribd.com/document/508241404/Ralph-Baric-Statement-to-The-Fact-Checker

Proximal Origin Draft. https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/SSCP-Drafts-of-Proximal-Origin.pdf

Andersen et al. 2020. “The Proximal Origin of SARS-CoV-2.” Nature Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0820-9

Cockrell et al. 2017. “Efficient Reverse Genetic Systems for Rapid Genetic Manipulation of Emergent and Preemergent Infectious Coronaviruses.” Methods in Molecular Biology. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6964-7_5

Donaldson et al. 2008. “Systematic Assembly and Genetic Manipulation of the Mouse Hepatitis Virus A59 Genome.” Methods in Molecular Biology. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59745-181-9_21

Cooke, Lucy. 2021. “The Batty, Explosive History of Bats in the Military.” The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/animalia/wp/2018/07/02/the-batty-history-of-bats-in-the-military-and-why-this-new-idea-just-might-work/

“U.S. Patent For Compositions of Coronaviruses With A Recombination-resistant Genome Patent (Patent # 7,618,802 Issued November 17, 2009). https://patents.justia.com/patent/7618802

Epstein et al. 2020. “Nipah Virus Dynamics in Bats and Implications for Spillover to Humans.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2000429117

Rosenke et al. 2020. “Defining the Syrian Hamster as a Highly Susceptible Preclinical Model for SARS-CoV-2 Infection.” EMI. https://doi.org/10.1080/22221751.2020.1858177

No Syrian hamster research at the WIV https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C44&q=syrian+hamster+wuhan+institute+of+virology&oq=syrian+hamster

De Wit et al. 2011. “Nipah Virus Transmission in a Hamster Model.” PLoS. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001432

U.S.R.T.K. NIH batch #61 (10.7.24). Pages 497 of 520. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/NIH-FOIA-Request-56077-March-Production_Redacted.pdf

Van Doremalen et al. 2020. “Aerosol and Surface Stability of SARS-CoV-2 as Compared With SARS-CoV-1.” New England Journal of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmc2004973

Greenfieldboyce, Nell. 2020. “Scientists Probe How Coronavirus Might Travel Through the Air.” NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/04/03/825639323/scientists-probe-how-coronavirus-might-travel-through-the-air

Bazant et al. 2021. “A Guideline to Limit Indoor Airborne Transmission of COVID-19.” PNAS. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2018995118

U.S.R.T.K. Colwell emails with EcoHealth Alliance staff (11.18.20). Page 292 of 466. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Biohazard_FOIA_Maryland_Emails_11.6.20.pdf

Calishera et al. “Statement in Support of the Scientists, Public Health Professionals, and Medical Professionals of China Combatting COVID-19.” The Lancet, February 19, 2020. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30418-9/fulltext

U.S.R.T.K. Baric emails batch #2: (2.17.21). Page 115, 116 & 182 of 332. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Baric-Emails-2.17.21.pdf

Intercept FOIA of U01AI151797 NIAID grant in September 2021. https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/21055988/risk-zoonotic-virus-hotspots-grant-notice.pdf

U.S.R.T.K. DoD USU batch #4 (7.8.24). Page 1487 of 1967 pages. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Q1-Broder-3rd-round-combined.pdf

Dilanian et al. “Report says cellphone data suggests October shutdown at Wuhan lab.” NBC. 2020. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/national-security/report-says-cellphone-data-suggests-october-shutdown-wuhan-lab-experts-n1202716

Tan et al. 2020. “A SARS-CoV-2 Surrogate Virus Neutralization Test Based on Antibody-mediated Blockage of ACE2–spike Protein–protein Interaction.” Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-0631-z

U.S.R.T.K. ongoing lawsuit with UNC. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/USRTK-v-UNC-Summary-Judgment-Order-22CVS000463-670.filed_.pdf

Wan et al. 2020. “Receptor Recognition by the Novel Coronavirus From Wuhan.” Journal of Virology. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00127-20

Xie et al. 2020. “An Infectious cDNA Clone of SARS-CoV-2.” Cell Host & Microbe. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.004

U.S.R.T.K. DIA presentation pages 17-18. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/6-20200625-SARS-CoV-2-Genome-Analysis.pdf

Ge et al. 2016. “Coexistence of Multiple Coronaviruses in Several Bat Colonies in an Abandoned Mineshaft.” Virologica Sinica. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12250-016-3713-9

Letko. Coronavirus cell entry. 2024. https://videocast.nih.gov/watch=55222

Letko et al. 2020. “Functional Assessment of Cell Entry and Receptor Usage for SARS-CoV-2 and Other Lineage B Betacoronaviruses.” Nature Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-0688-y

Molteni, Megan. 2020. “Can a Database of Animal Viruses Help Predict the Next Pandemic?” WIRED. https://www.wired.com/story/can-a-database-of-animal-viruses-help-predict-the-next-pandemic/

Bloom. 2021. “Recovery of Deleted Deep Sequencing Data Sheds More Light on the Early Wuhan SARS-CoV-2 Epidemic.” Molecular Biology and Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab246

Eskild et al. 2022. “Prevalence of Antibodies Against SARS-CoV-2 Among Pregnant Women in Norway.” Epidemiology and Infection. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0950268822000073

Basavaraju et al. 2020. “Serologic Testing of US Blood Donations.” Clinical Infectious Diseases. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa1785

Williamson et al. 2021. “Continuing Orthohantavirus Circulation in Deer Mice in Western Montana.” Viruses. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13061006

U.S.R.T.K. NIH batch #35 (2.1.24). Pages 114 & 489 of 501. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/NIH-FOIA-Requests-56077-January-Production_Redacted.pdf

Caserta et al. 2023. “White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus Virginianus) May Serve as a Wildlife Reservoir for Nearly Extinct SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern.” PNAS. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2215067120

Martins et al. 2022. “From Deer-to-Deer: SARS-CoV-2 Is Efficiently Transmitted and Presents Broad Tissue Tropism and Replication Sites in White-tailed Deer.” PLoS Pathogens. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1010197

Moreira-Soto et al. 2022. “Serological Evidence That SARS-CoV-2 Has Not Emerged in Deer in Germany or Austria During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Microorganisms. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms10040748

U.S. Senator's letter listing DARPA Defuse vendor. “NIH Rocky Mountain Lab - Vincent Munster.” https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/media/reps/dr-paul-sends-letters-to-fifteen-federal-agencies-after-discovering-their-knowledge-of-risky-defuse-project/

Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Pandemic. 2023. https://oversight.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/2023.03.05-SSCP-Memo-Re.-New-Evidence.Proximal-Origin.pdf

Fauci and Baric's joint presentation on March 10, 2020.

U.S.R.T.K. NIH batch #75 (10.24.24). Fauci’s 2017 presentation. https://usrtk.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Responsive-Documents-62469.pdf

Washington Post. 2021. “U.S. Controls on Experiments With Supercharged Pathogens Have Been Undercut Despite Lab-leak Concerns.” https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/interactive/2021/a-science-in-the-shadows/

Sandbrink et al. 2021. “Safety and Security Concerns Regarding Transmissible Vaccines.” Nature Ecology & Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01394-3

Reeves, Guy. Max Planck self-spreading vaccine references. http://web.evolbio.mpg.de/HEVIMAs/

Letko et al. 2020. “Bat-borne Virus Diversity, Spillover and Emergence.” Nature Reviews Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0394-z

Sheen et al. 2025. “Design of Field Trials for the Evaluation of Transmissible Vaccines in Animal Populations.” PLoS Computational Biology. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1012779

On June 27, 2025, the SAGO committee responded on page 46:

A response to the World Health Organization and their SAGO report

The SAGO report referenced my book!

This is not only the most plausible origin of the virus but also a fact that even an American mink would accept. A virus that was designed and manufactured in the United States was sent to Wuhan, China, for testing in horseshoe bats.

Jim has nailed it.

The devil and his minions.

The minions brought fear. The devil brought the poison.

Virus or no virus, getting billions of people to have their bodies genetically reprogrammed to produce their own poison is quite a feat.

(S-protein besieges all ACE2 receptors for life + bonus gift from the manufacturers).

The question remains, however: was it the plan from the beginning to harm people with

injections—and was the fear of the virus just a precursor?

My sister's friend heard this from her hairdresser:

The chimeras were developed to create fear. The real weapon was the “protection” against the virus. Right from the start. So simple - so effective. Humans are strange creatures.

And the manufacturers only looked half-heartedly. The promise of a lifetime's worth of sales puts all doubts to rest. Here is the copy of the evil virus. "Take that Spike. It's the easiest". "Yes - no problem. Thanks for the file. We don't have the time". And off we go with the production. And earning money.

But it's probably just nonsense.

has anyone ever wondered where all these small vials suddenly came from? you can't just ramp up production on this scale in a few weeks. it's not possible. they had already been produced for a long time. they were in stock - ready to be called off. and then the starting signal came - fill and distribute.

But what the heck - it's done.