The Origins of USAID Predict

Excerpt from previous post #7

With USAID in the news, now is a good time to revisit our one-year-old post on EcoHealth and its Predict project. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), often called a “soft-power CIA,” operates with a $50 billion budget compared to the CIA/DNI/NSA’s $75 billion—each comprising roughly 1% of the total US $6 trillion expenditure.

Jeff Sachs and Mike Benz describe USAID as a mix of good and bad—funding everything from education and malaria prevention to Afghanistan’s opium trade and a “Cuban Twitter” designed to incite unrest.

USAID, along with Republicans, has funded transgender art abroad. USAID, like Canada, paid for $10,000 subscriptions to the German-owned Politico. Much of its foreign aid goes to Ukraine, where only half of the $177 billion allocated by Congress reached Ukraine, according to President Zelenskyy.

Cynics view foreign aid as a domestic jobs program. The funds come with strings attached, requiring recipients to spend US dollars on American goods—whether military tanks, lab equipment, or bat samples. While Fauci’s NIAID funded the collection of RaTG13 in 2013, USAID Predict was operating just miles from the Mojiang mineshaft—where three miners died in 2012.

Within USAID, the $213 million Predict program aimed to prevent pandemics but functioned as a Hoover vacuum for foreign pathogens. Of that total, $60 million went to EcoHealth, but only $800,000 reached the Wuhan Institute of Virology. US universities benefited the most since foreign pathogens made their way to American campuses. DARPA Preempt team member

had a good summary:When my colleagues were catching bats across SE Asia, they wanted to surveil wildlife and find new viruses. That was the goal of most wildlife virology work. From the USAID’s PREDICT program or the Wellcome Trust + Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation supported Global Virome Project (supported through CEPI) to the DARPA PREEMPT grant that I was a part of or the DEFUSE proposal to the same DARRPA PREEMPT program, everyone wanted to find wildlife viruses, characterize their diversity, and study their functions in the labs.

When you catch a bat in Asia, especially when you’re a scientist catching bats with the express purpose of finding viruses in bats, you can’t just ship a sample with live viruses overseas. On one hand, you can freeze your sample, but that requires getting dry ice to whichever remote, humid, buggy location you’re catching bats from and setting up the logistics of moving samples smoothly without risk of the samples warming up. RNA viruses like CoVs are very fragile things and the half life of infectious virions is on the order of 1 day at room temperature.

Peter Daszak budgeted thousands of dollars for liquid nitrogen, or what was called the “cold chain” in DARPA Defuse:

Samples will be preserved in a viral transport medium, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen dry shippers, and transported to partner laboratories with a maintained cold chain under strict biosafety protocols.

Daszak continued in the 2018 DARPA Defuse proposal:

We will test and validate viral diversity predictions using data from >10,000 previously collected bat samples from 6 Asian Counties under our USAID-funded PREDICT project.

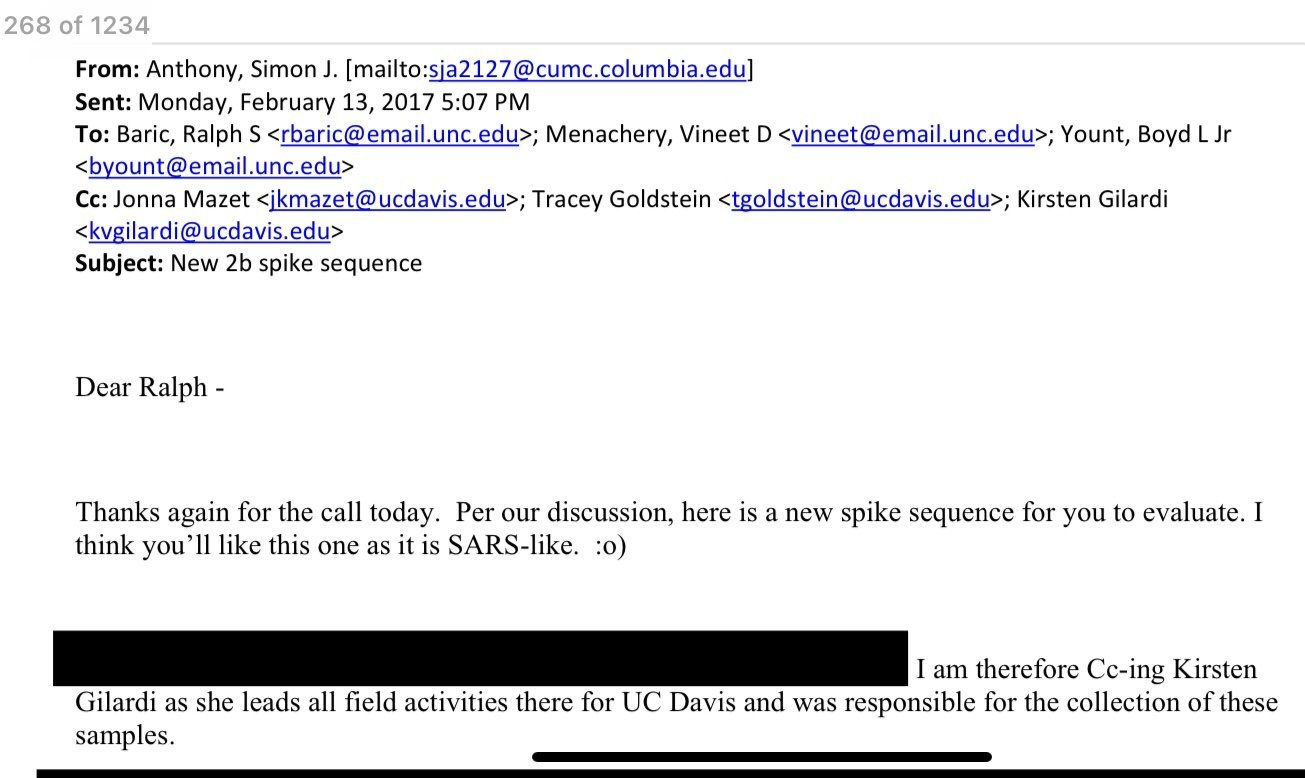

Most lab leak proponents assume all relevant SARS2-like samples were shipped to Wuhan. However, Predict funded the collection of bat samples that were sent to US universities—for example, coronaviruses from Bangladesh were shipped to Montana State University. In 2013, Tony Fauci, Ralph Baric, Vincent Munster, and Peter Daszak discussed bat sample logistics (video link at 3:50:00).

The Predict field team operated under USAID’s Emerging Pandemic Threats (EPT) Program. Officially, EPT was launched during the Obama administration in response to the 2009 H1N1 outbreak. But its true origins trace back to 2005, with Peter Daszak’s deputy, Billy Karesh.

University bureaucrats depend on large NIH grants, as they charge facilities and administrative (F&A) fees in the 60–70% range, whereas EcoHealth had a lower rate of 30–40%. This made EcoHealth an efficient passthrough for biodefense research. As of 2025, neither Daszak nor Karesh appears on the EcoHealth website—yet both were instrumental in creating the USAID program.

The following is an excerpt from Substack Post #7:

The collection of Ralph Baric’s SHC014 bat sample was funded by an obscure State Department program called USAID Predict. A year later, Shi Zhengli traveled to the Mojiang mine, using NIAID’s R01AI110964 funding, to collect RaTG13. Shi sequenced and uploaded the genome to NIAID’s Genbank server in 2016 and 2018. Was a SARS1 bat vaccine a solution to this potential SARS2 problem?

Origins of One Health and USAID Predict

The current head honchos of EcoHealth use conservation as a funding source for their global travels. They sell exotic animal samples to US academia. They are globetrotting veterinarians with business-class expense accounts on the taxpayer's dime.

These four (nonprofit) EcoHealth officers collectively paid themselves $1.1 million in 2018. Most of the $18 million in 2018 revenue was from one program: USAID Predict. The profit margins are incredible when subcontracting grant work to cheap Chinese labor. For example, the “pencil dust” R01 grant was worth $600,000 per year over five years, but EcoHealth only paid out $120,000 to the WIV. Why? In the DARPA Defuse proposal, we learned the WIV labor rate was as low as $7/hour, but the bid was worth $14 million to EcoHealth, Duke, and UNC. The Chinese airfare, per diem, and lodging for bat sampling were pennies out of millions of dollars worth of biodefense grants.

Daszak hired Jon Epstein from Colombia as adjunct faculty in 2003 so he “would not have to pay for subscription fees to scientific publishers.” Jon followed in Daszak’s steps and first appeared in a 2006 NYT article blaming men, not bats. Daszak also hired Kevin Olival in 2011, but only after Daszak asked NIAID to approve Kevin’s CV. NPR followed Kevin to Asia in 2017, so they logically asked him about the SARS2 in 2020.

Daszak’s longtime colleague, Billy Karesh, had a similar childhood. He grew up in South Carolina, raising orphaned birds, squirrels, and raccoons. He released them when they were old enough to survive on their own. Karesh worked as a zookeeper and settled in at the Bronx Zoo in 1989. Ten years later, he became the Director of the Field Veterinary Program. The Bronx Zoo was owned by the 100-year-old Wildlife Conservation Society.

“What I do for a living is not fun, at least not while I'm doing it.” Believe him. He figures that only 5% of his travel time is spent working on animals directly; the remainder is spent dealing with the enigmatic rules and customs of third world bureaucracies. Animals do not make the work dangerous, he says; what does is having to travel '“through the middle of rebel-infested nowhere and mediating my fate with teen-age soldiers equipped with better weapons than educations.” But his love for the job emanates from every page. He confesses that he's addicted to the adrenaline rush.

Karesh was a wildlife veterinarian traveling the globe 10 months out of the year. It was a shoestring budget but funded by the non-profit Wildlife Conservation Society (do not confuse Daszak’s Wildlife Trust with Karesh’s WCS, but it’s a future partner to USAID Predict).

Dr. Karesh described once trying to get a research grant for surveillance of animal diseases that infect humans, known as zoonoses. The National Institutes of Health told him to apply to the Department of Agriculture, he said, and officials there sent him to the Fish and Wildlife Service, which told him it had no mandate to study disease.

“Then we went to Homeland Security, and they understood what we were talking about,” Dr. Karesh said. “But they said: 'You're an orphan. No one does this.' And in their rankings, we're lower than people trying to blow up the subway in New York.”

After spending years in a zoo and out in the bush, Karesh thought human health, livestock health, and animal health were an “artificial division created by people.” He officially coined the term “One Health” in 2003 during an Ebola outbreak in Africa. He told a reporter that “human or livestock or wildlife health can't be discussed in isolation anymore; there is just one health. And the solutions require everyone working together on all the different levels.”

In 2005, Karesh wrote a Foreign Affairs article about this One Health concept. Diseases “shared a worrisome key characteristic: the ability to cross the Darwinian divide between animals and people.” He noted, “The world’s not flat; it’s a mixing bowl.” Therefore, a “broader, more democratic approach is needed, one based on the understanding that there is only one world -- and only one health.”

The following year, Karesh and his WCS colleagues launched a series of global conferences with the theme “One World—One Health.” What started out as the WCS avian influenza network eventually “morphed into the USAID Emerging Pandemic Threats (EPT) Program,” which now included Daszak’s Wildlife Trust.

By 2009, Daszak was coordinating a “very well-funded project between five universities, which kind of took over” the Wildlife Trust. At the same time, Daszak took over as president of the trust, and some of those universities became members of the USAID EPT program or Predict.

Months later, Daszak rebranded the 30-year-old Wildlife Trust as EcoHealth Alliance and hired Karesh as his loyal #2 lieutenant. Karesh’s capabilities in the field and connections with the local press helped build EcoHealth. They wanted a “dual focus on local wildlife conservation and its ongoing leadership in the area of conservation medicine, and the relationships between animal ecosystems and human health.” The latter of the two was much more lucrative. Karesh called it a $1B “investment” by the US government.

Everyone remembers 9/11, but everyone forgets Amerithrax. A US government scientist (allegedly) mailed airborne anthrax to political targets and (successfully) increased biodefense funding. One of the many “weaponized” letters was addressed to Tom Daschle’s Senate office. In 2017, Daschle headlined an EcoHealth event at the Cosmos Club in Washington, D.C. He told the D.C. crowd that “biodefense is an issue important to me because my office was a target of the anthrax attacks 16 years ago.” Daschle now heads the Blue Ribbon Biodefense commission with Joe Liebermann and Karesh.

The “military-academic complex of scientists” began after 9/11. Fauci’s NIAID secured most of the biodefense money, which had a “corrupting” effect. As an example, Daszak, Linfa Wang, Dani Anderson, and the founder of Predict, Dennis Carrol, all quoted Donald Rumsfeld’s “known unknown” Iraq War line. Rumsfeld was referring to terrorism, but Daszak was referring to the problem that USAID Predict helped create: too many virus samples.

In 2008, Daszak mentioned “bioterror” agents in his NIAID grant. During a Blue Ribbon Biodefense conference, Daschle asked Daszak if we cry wolf too often. Daszak responded, "I would say we've not cried wolf with Ebola, SARS, and influenza; rather, I would say that we've dodged bullets.”

Project Bioshield was all about biodefense vaccines. Since polio only infects humans, vaccines easily eradicate it. However, zoonotic pathogens like Ebola, SARS, and MERS can “jump species” and hide in a “reservoir host” that harbors the disease without illness. USAID Predict, along with modern sequencing technology, helped virologists narrow down that huge list of mammalian suspects to bats.

USAID Predict

Daszak’s 2019 CREID CV brags to Fauci’s NIAD that “I have also led large contracts from USAID (institutional lead on $75 million PREDICT-1 and $138 million PREDICT-2).” The State Department sponsored the USAID Predict program. It used US universities (e.g., Linfa’s alma mater, UC Davis) as a friendly face in foreign countries. It also used American newspapers to scare the wallets out of the taxpayers’s pockets.

USAID wanted to “detect, prevent, and respond to future biological threats.” The idea was to collect virus samples from around the developing world and ship them back to US labs to create “countermeasures.” This term may sound nefarious, but dorks, not spooks, ran the Predict program. It was a bunch of do-gooders with good intentions but bad outcomes.

Andrew Huff, the former EcoHealth employee, recalled, “While reading about the EcoHealth organization, I fell in love with the mission.” He called the Predict program “sexy” and wanted to work in the big-money modeling department. It included 50 remote EcoHealth coders, creating fancy Bayesian models for dull academic reports.

USAID Predict was a classic foreign policy boondoggle that gave local tax dollars away to foreign entities. But the money came with strings attached since they shared samples with American virologists. USAID Predict funded nearly every significant bat sample ever collected, so below is a list of projects:

The three dead Mojiang miners in April 2012, where RaTG13 (96% similar SARS2) was collected in 2013, hence the name RaTG13.

The WIV1 bat sample was later shipped to the University of North Carolina (UNC) and Rocky Mountain Lab for infection experiments in Egyptian fruit bats. This 2018 project was the beginning of DARPA Defuse in Montana.

Shi emailed Baric the SHC014 sample in 2011 so he could resurrect the virus using his exclusive reverse genetic system. This led to their controversial 2015 paper, which kept Fauci up until 3 AM in early 2020.

The Rp3 sample was collected in 2004. It was the 3rd sample taken from a Rhinolophus pearsonii bat and 92% similar to SARS1. It was used in the coverup email by Baric and Daszak in early 2020.

The RshSTT182 sample was collected in 2010 from Cambodia, and 93% similar to SARS2. In short sections, the Cambodian sample was closer to SARS2 than RaTG13 (think Baric’s consensus sequence).

The RacCS203 sample was 94% similar to SARS2. It was collected by USAID Predict in Thailand and was most similar to China’s RmYN02 at the S1/ S2 boundary. The Thai sample was from Linfa’s paper and edited by Dani, who both referenced Baric’s “consensus virus” in 2019.

As a Washington Post reporter summarized about USAID Predict:

It pays for the transportation back to various laboratories. Some of these samples, over the years, have been brought back to institutions here in the United States where they are analyzed, to a great extent, by US-based researchers.

Dawn Zimmerman of the Smithsonian Museum worked on the USAID Predict program in Kenya. The video above shows you where all these bat samples ultimately wind up: Washington, D.C. The excerpt below is from David Quammen’s book Spillover regarding the Predict project.

When John Epstein takes serum from flying foxes in Bangladesh, when Alexei Chmura bleeds bats in Southern China, some of those samples go straight to Ian Lipkin.

EcoHealth sent their Chinese bat samples to Ian Lipkin’s lab at Columbia. Lipkin’s lab forwarded the coronavirus samples to Baric’s Chapel Hill lab, which just downloaded the sequence and used reverse genetics to create a live Chinese virus in North Carolina. “And you (Baric) had developed a reverse-genetics technique that allowed you to synthesize those viruses from the genetic sequence alone? Yes”

The Predict program was a Hoover vacuum in every bat cave, sucking up every bat sample, trying to “predict” or “forecast” the next zoonotic spillover event. Kevin Olival, a longtime employee of EcoHealth, best described the program. “I've spent the last 10 years working with governments under (PREDICT with NIAID and DTRA funding) building the trust needed to share viral sequence and other bio-surveillance data, so I understand the importance and challenges of making this happen and getting it right.”

The former EcoHealth employee, Andrew Huff, grew disillusioned over time, noting that “every virus discovered was an easy peer-reviewed publication and another bullet point for their CVs.” The entire program was pseudoscience, but “who wouldn’t enjoy a swanky scientific job traveling the planet, acting as a diplomat, and making deals?”

A Washington Post reporter described virus hunting as a “chain or risk” with the potential for “catching your experiment” via needlestick, bat bite, mishandling samples, etc. In 2012, a 25-year-old American researcher became sick and was hospitalized for two weeks after sampling Egyptian fruit bats in Uganda.

Why DTRA?

The Pentagon’s Defense Threat Reduction Agency was EcoHealth's second-largest government source of money, behind USAID Predict. In 2013, Daszak booked the Cosmos Club for DTRA head Andy Weber.

Weber had previously invited a junior senator from Illinois, named Barack Obama, to a Soviet-era bioweapon lab in Ukraine. Senator Obama recalled from his 2005 Kyiv trip, “I saw test tubes filled with anthrax and the plague lying virtually unlocked and unguarded — dangers we were told could only be secured with America’s help.” In 2009, President Obama declared the H1N1 flu an emergency and supported the creation of the USAID Predict program.

Read the rest here:

On the anthrax attack perpetrator(s), please insert "alleged" or "accused" before Bruce Ivins's name as the scientific evidence was not conclusive that he mailed the letters (according to the National Academy of Science) nor that he could even fabricate those highly refined, aerosalized anthrax spores sent in those letters. (according to the UN biological weapons expert Richard O. Spertzel.