In 2012, natural-origin journalist David Quammen foreshadowed the COVID-19 role of EcoHealth, DARPA, DoD, USAID, WHO, bioterrorism, and bats.

To a considerable degree, such things are already being done. Ambitious networks and programs have been created by the WHO, the CDC, and other national and international agencies to address the danger of emerging zoonotic diseases. Because of concern over the potential of “bioterrorism,” even the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA, whose motto is “Creating & Preventing Strategic Surprise”) of the U.S. Department of Defense have their hands in the mix. These efforts carry names and acronyms such as the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN, of WHO), Prophecy (of DARPA), the Emerging Pandemic Threats program (EPT, of USAID), and the Special Pathogens Branch (SPB, of the CDC), all of which sound like programmatic boilerplate but which harbor some dedicated people working in field sites where spillovers happen and secure labs where new pathogens can be quickly studied. Private organizations such as EcoHealth Alliance (led by a former parasitologist, Peter Daszak) have also tackled the problem. “You come to this blind room, and the first thing you see is hundreds of dead bats.”

For example, Daszak’s colleague, Vincent Munster of Rocky Mountain Lab, updated the WHO on his fruit bat vaccine in 2022.

Quammen’s post-pandemic 2022 book, Breathless, ironically provided insight into a Wuhan lab leak:

University of Arizona virologist Michael Worobey and a group of colleagues wanted to pinpoint the first arrival and track the earliest spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Europe and North America. They suspected that the answers might be different from what other studies proposed. They knew that the first confirmed case in the United States was detected in Snohomish County, Washington, on January 19, 2020, in that man who flew home from a family visit in Wuhan.

They knew that some evidence pointed toward the Snohomish man as perhaps America's Patient Zero and that he might have infected others, who infected others, in chains of cryptic transmission during late January and early February of 2020, from which the virus spread to California and British Columbia and Connecticut and onward, making the Seattle area the epicenter of the North American epidemic. The Snohomish man's viral genome sequence, designated WA1, as in “Washington case 1,” became an object of close scrutiny.

I highlighted this man’s travels (and his WA1 isolate) in Chapters 2 and 27 of my book. He was the return-to-sender address. He provided proof of a Rocky Mountain Lab origin, meaning Egyptian fruit bats, American deer, deer mice, and mink were WA1 transmission models. It was the basis of the book’s scientific survey (virologist Angie Rasmussen has the latest results). Quammen continues with a similar WA1 story for Germany:

Worobey et al also knew that the first European case was in a woman who lived in Shanghai, got infected there by her parents when they visited from Wuhan, then flew for business to Munich and connected to a town nearby, where she infected a man, one of her fellow employees, at an automotive supply company called Webasto, a maker of sunroofs and heaters. That man tested positive on January 27, 2020, by which time the woman— who has been called Europe's Patient Zero, though she only bounced into Europe long enough to be a transmitter —had flown back to Shanghai, where she worsened and was hospitalized. The German man was hospitalized, too, in isolation, and his virus was sampled and sequenced.

That sequence, labeled BavPat1, as in “Bavarian Patient 1,” is almost famous. It differs by just one nucleotide, among nearly thirty thousand, from the founding virus of the lineage that swept across Europe and the United Kingdom in the early months of the pandemic and became known as lineage B.1. (The B in that B.1 did not stand for Bavaria, however; it becomes important with the rise of notorious variants.) Worobey's group also knew of a study implying that the German case of January 27 seeded the Italian outbreak that flared in March, from which the virus also spread to France, Mexico, and the US, causing the first wave of terrible mayhem, overtaxed hospitals, and dead bodies stored in cooler trucks for lack of mortuary capacity. From that earlier study, a broader narrative took hold of Webasto as the source of the European and American epidemics that reached even the automotive trade press. Putting on a sunroof manufacturer was a terrible burden, and Webasto denied it.

To summarize, Covid was probably circulating in Europe (and pregnant Norweigan women) by December 2019. However, Europe’s first diagnosed case was a Chinese woman who visited her company’s headquarters in Bavaria, Germany, from Shanghai, China, on January 20, 2020. She had been infected with SARS2 in Shanghai (after her parents had visited from Wuhan). She transmitted Covid to a German man who tested positive on January 27 and whose viral genome (“BavPat1”) was isolated in Germany on January 28.

The German Patient 0 isolate is Germany/BavPat1/2020 or Germany/MUC-IMB1/2020. It was tested on several German lab animals (pigs, ferrets, chickens, and fruit bats) at Friedrich-Loeffler-Institut (FLI), the oldest virological research institution in the world. FLI is located in Riem on an island in the Baltic Sea.

In 1898, after German virologist Friedrich Loeffler inadvertently infected the whole northern region of Greifswald with foot-and-mouth disease, he moved his institute to a safer location on the island of Riems in 1910. The Third Reich even used FLI to research bioweapons.

FLI also has a live colony of Egyptian fruit bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus). Although these bats’ immune system could be used for bioweapons research, bat virologists call them “sky puppies.” Unlike Chinese horseshoe bats, they are easy to handle and breed. FLI established a colony of Egyptian fruit bats in 2013.

In 2020, FLI inoculated nine Egyptian fruit bats with SARS2 (i.e., BavPat1) and housed them with three others. All the inoculated bats became infected, and the virus spread to one of the three cage mates, but none became ill. The results confused the century-old institute:

“Our data suggest that intranasal infection of Rousettus aegyptiacus could reflect reservoir host status and therefore represent a useful model, although this species is certainly not the original reservoir of SARS-CoV-2 because these bats are not present in China, the epicenter of the pandemic.”

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanmic/article/PIIS2666-5247%2820%2930089-6/fulltext

Egyptian fruit bats are called a “non-natural” reservoir host for SARS2. And “these bats” were used in Rocky Mountain Lab, which is the “epicenter” for self-spreading bat vaccines.

https://usrtk.org/covid-19-origins/colorado-state-university-documents-on-bat-pathogen-research/

In September 2020, Billy Bostickson of DRASTIC was a prophet by asking, “What is your opinion on this new finding from Germany that fruit bats can be infected, replicate and transmit SARS-CoV-2? The ferret results are not surprising, but the bat results are new.” Fellow DRASTIC member Daoyu blew it off because it wasn’t the best known ancestral strain, but Billy replied, “I'm not sure that you can write off the results of this experiment that easily. I suspect that certain bat species can be infected, replicate and transmit SARS-COV-2, which stands to reason given their use as lab animals for precisely such experiments according to our research.”

In early 2021, Billy Bostickson started a lengthy Twitter thread about live Chinese bats at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. The thread ended with live Egyptian fruit bats at the US CDC in Atlanta, Georgia. The Egyptian fruit bats were imported from Africa and used for Marburg research, which was ironically named after Marburg, Germany, where the lethal virus leaked from a lab.

The Robert Koch Institute in Germany, akin to the US CDC, was also fascinated by Egyptian fruit bats. These bats served as the lab rats for German virologists like Christian Drosten, who even visited self-spreading bat vaccine labs.

By 2011, the US CDC lab had established a breeding colony to produce disease-free bats. These bats were captive-born and bred Egyptian fruit bats, which made them easier to handle under BSL4 conditions. These African bats were “first-generation” American lab bats raised in Atlanta and fed watermelons.

In 2013, Ralph Baric and Vincent Munster followed the lead of the US CDC. They spoke off-camera, and Fauci walks away toward the end.

Munster is talking off-camera to Baric, who proposed to infect Munster’s bats with his coronaviruses. This video clip summarized my book’s question: Why does this Old World virus called SARS2 love New World lab animals?

By 2018, Baric and Munster had executed the 2013 plan, infecting New World lab bats with Old World viruses. They co-published the negative result with a wish list of items, SARS-Like Coronavirus WIV1-CoV Does Not Replicate in Egyptian Fruit Bats (Rousettus aegyptiacus):

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6316779/

While ACE2 was expressed in bat intestine and respiratory tract tissue, similar to humans, we observed very limited evidence of virus replication and seroconversion. These data demonstrate that WIV1-CoV restriction in the Egyptian fruit bat was not at the receptor level. However, in this study, very limited evidence of virus replication or seroconversion was detected. It is currently unclear why WIV1-CoV seems unable to replicate efficiently in Egyptian fruit bats. It is possible that the WIV1-CoV S glycoprotein is not processed by surface or intracellular proteases, which have been shown to be important host restriction factors during coronavirus entry [12,13].

Intracellular proteases was Baric language for a furin cleavage site. Reference #13 was German virologist Christian Drosten. Their “initial study indeed suggested that efficient SARS-CoV spread might depend on SARS-S activation by furin.”

An anonymous scientist informed me, “Furin is certainly present throughout the endomembrane systems of mammalian cells (e.g., endoplasmic reticulum), allowing the virus to be processed during the intracellular trafficking process. They were aware of their actions when they included that furin cleavage site.”

In 2018, Baric and Munster referenced Drosten in #15:

A recent study generated an annotated full genome for Egyptian fruit bats and used this to show greatly expanded natural killer cell receptors, MHC class I genes and type I interferons. It has been hypothesized that these factors allow greater tolerance to viral infection [15], resulting in prolonged infection but limited inflammation which has been described for Egyptian fruit bats inoculated with Marburg virus.

Drosten had provided bat cells for paper #15, which involved Fort Detrick and Boston’s BSL4:

The Rousettus aegyptiacus cell line (Egyptian fruit bat) RoNi/7.1 was generated by M.A. Müller and C. Drosten, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany with funds from the EU-FP7 ANTIGONE (no. 278976) framework and the German Research Council (DR 772/10-2).

https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(18)30402-1

The #15 bat immunology paper focused on MHC Class I, a key immune mechanism that Baric fixated on in DARPA Defuse. MHC Class I helps the mammalian immune system find and destroy infected cells by showing pieces of proteins to killer T cells. Some viruses, like SARS2, hide from the immune system by blocking MHC Class I from working. This is another weird Covid pathology in humans:

In 2018, Baric and Munster referenced Drosten again in #18:

We observed cleavage of MERS Spike glycoprotein in our pseudotypes, whereas neither SARS Spike or WIV1 Spike glycoprotein were cleaved. This matches closely to what has been reported on proteolytic activation of MERS Spike and SARS Spike glycoprotein and further supports the validity of the use of pseudotypes. Whereas MERS Spike glycoprotein is processed by host proprotein convertases in virus-producing cells before virus-cell entry [18], SARS Spike glycoprotein processing by these convertases is absent or inefficient [19]. Our results suggest that like SARS Spike glycoprotein, WIV1 Spike glycoprotein does not get cleaved by host proprotein convertases.

In reference #18, Drosten et al discussed the furin cleavage site in MERS several times (MERS strains have an FCS, but SARS-like strains don’t). However, they noted how “inefficient” SARS1 was without a furin cleavage site.

For Baric and Munster, inserting a furin cleavage site into a SARS-like virus was easy. But the logistics of testing it on the natural reservoir host is difficult. Enter their DARPA Defuse colleague, Linfa Wang:

It’s not easy to work with captive horseshoe bats, as Linfa Wang discovered. In 2005, the molecular virologist wanted to infect the animals with the virus that had caused the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) a few years earlier to find out whether it would evolve to grow well in the bats. Working in a maximum-biosecurity lab, he and his team at the Australian Animal Health Laboratory struggled to feed the small insectivores while wearing full-body protective gear. “We had to fly small worms in front of them while wearing these spacesuits,” recalls Linfa Wang, who is now at the Duke-NUS Medical School. In the end, he says, his technicians balked before they had publishable results. But the potential payoff of such experiments was alluring, because of mounting evidence that bats served as reservoirs for emerging viruses that could kill humans.

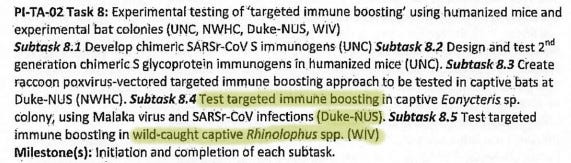

This is why they proposed wild-caught Chinese horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus) in DARPA Defuse.

After losing DARPA Defuse in early 2018, Baric and Munster concluded in late 2018:

Therefore, it would be interesting to perform an experimental inoculation study using Chinese horseshoe bats, from which WIV1-CoV was originally isolated, to investigate if more efficient virus replication and shedding can be observed in these animals.

Now we know why the SARS2 furin cleavage site loves Egyptian fruit bats. Their furin cleavage site was a biological shortcut for overcoming the ACE2 barrier that exists between Chinese horseshoe bats and Egyptian fruit bats. Unfortunately, as they noted in 2018, “ACE2 was expressed in bat intestine and respiratory tract tissue, similar to humans.”

The ancestral WA1, and early BavPat1 strains, proved a Wuhan area lab leak and “NIH Rocky Mountain Lab” origin. Unlike FLI in Germany, RML in Montana is sitting on unpublished data regarding their Egyptian fruit bat colony. I don’t know about you, but Munster sounded nervous in that 2023 Science Magazine article.

For new lab leakers wondering how this Montana concoction wound up in Wuhan:

May I say an extremely insightful piece on the origin of SARS-CoV-2? I would urge that anyone interested in the subject must read Jim's book, which is the best work on the subject.

To make things easier to understand without changing the truth, Baric made a novel synthetic virus by adding 4 amino acids (furin cleavage site) that allowed it to infect Egyptian bats that were previously immune to other coronaviruses, including RaTG13 that was found by the Chinese Bat Lady. The Chinese Bat Lady then wrote about this virus in the third week of January 2020, making it clear that her virus, while very similar to SARS-CoV-2, did NOT have the furin cleavage amino acids. This was a signal to the world that she had not designed nor leaked SARS-CoV-2 from her lab, which was distinct from the WIV lab.The virus created by Baric was subsequently made airborne by Munster, who had the necessary expertise to do so. The airborne Baric/Munster virus was transported to the WIV laboratory to be tested in Chinese horseshoe bats.

.interestingly, the first man to be detected with SARS-CoV-2 in Washington had travelled from Wuhan with a virus identical to the one recognised as SARS-CoV-2 by the CDC; the difference lay in only 3 nucleotides and one amino acid. The hospital admitted this patient who had been suffering from fever and cough for the past four days. He remained ill for 11 days, had a clear X-ray initially but developed atypical pneumonia around the 10th day, and had a course of heavy antibiotics for his fever.The same patient (remember the first reported in the USA) was administered an experimental drug on "compassionate" grounds; he had a magical transformation by the next day; he became entirely asymptomatic and was soon discharged from the hospital. This was the first advertisement for remdesivir to treat Covid, despite a paper on Ebola reporting mortality of 50% with the same drug (also published by the same journal).

https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMoa2001191

Let's now shift our focus to Munster, where he authored a piece in the New England Journal of Medicine on February 20, 2020, in which he goes to enormous lengths about surveilling the new virus from China and the effects of quarantine. He makes no mention of the virus's potential for airborne transmission! His expertise in the field of virology is widely known, which is why he received an invitation to be the chief of the Virus Ecology Section at NIAID.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2000929

If someone is still unable to grasp the chronology of events in the building of SARS-CoV-2, the explanation is not that the individual is incapable but rather is reluctant to.

So was it quite unlucky then that an animal to human spillover (horseshoe bat to Dani) happened when the horseshoe bat actually was not such a great candidate for transmission as say an Egyptian fruit bat would have been? (Hence the suggestion of a needle stick accident?) Or have I got that the wrong way around?